By Peter Makem

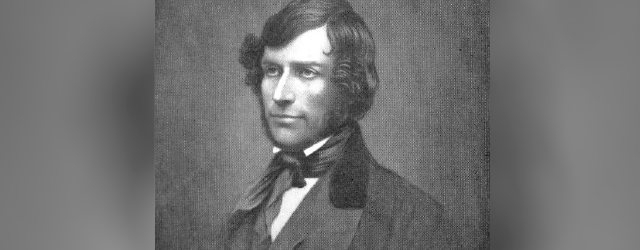

Over fifty years ago a statue was erected in Newry in honour of the Irish patriot John Mitchel (1815-1875) by some local politicians and leaders. A Newry GAA club around that time was named in his honor and a local street became John Mitchel Place.

Born near Dungiven in Co. Derry and reared in Newry where he practiced as a lawyer, he became a prominent Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist.

He went to live in Dublin in the early 1840’s where he became a leading member of both the Young Ireland movement and the Irish Confederation. He was on the staff of ‘The Nation’ newspaper but soon founded a more radical paper ‘The United Irishman’ which demanded total freedom from English domination, in the tradition of Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmett.

Aware of Mitchel’s influence, the British government introduced the ‘Treason Felony act’ in 1848 and because of his political statements he was charged with sedition before a packed jury and sentenced to 14 years transportation to a penal colony in Van Diemans land (Tasmania.)

He later escaped to the United States in the 1850s, and became a pro-slavery editorial voice, in various publications supporting the confederate states during the American Civil War, and where two of his sons died fighting for this cause. He returned to Ireland after the war and was elected to the aUK parliament for Tipperary in 1875, but was disqualified because he was a convicted felon. He died suddenly at the age of 60 that same year.

Apparently Mitchel made claimed that slaves in the southern United States were better cared for and fed than Irish cottiers, or industrial workers in English cities like Manchester. Many others have asserted this. But it was the racist undertones that are now causing big problems, claiming that negroes were “an innately inferior people”. “We deny that it is a crime, or a wrong, or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction.”

He claimed that slavery was inherently moral and “good in itself” and stated that he “promotes it for its own sake.” These views on slavery were largely rejected by the Young Ireland movement as a whole.

So in the ongoing drama of the ‘Black lives matter’ the celebrated statue to the Young Ireland patriot whose life’s ambition was the repeal of the Union with Britain is a source of controversy.

I remember reading a moving passage from his ‘Jail Journal’ when the ship was crossing the Indian Ocean en route to Tasmania, and he was looking up at the full moon above him and thinking that this same moon was shining down on his wife and children ten thousand miles away in their house in Newry. So the problem at present is how to relate his active patriotism and sacrifices with this blemish.

Many feel the statue should remain but a plaque be erected telling of this aspect of his history and leaving things at that. But then again, if the flaws of people’s personalities were all subject to various waves of opprobrium, would anybody be left standing?

Daniel O’Connell who seemingly had children all over the place, would be taken down in Dublin and the famous street renamed in such circumstances. ‘Black Lives Matter’ protesters in London were loud in their assertion that Churchill was a blatant imperialist racist and that his policies caused the death by starvation of three million people in India. And is not the statue of Cromwell proudly standing outside the houses of parliament in London?

Can anything be authentically named in honour of anybody when various misdemeanors are judged to outweigh heroic acts in the balancing act of the various times that one Ages’ hero is the villain of another, as they used to say here in the Troubles that one man’s freedom fighter is another’s terrorist.

The statue of John Mitchel was put up in Newry to keep his name alive. But it’s a strange way to be fighting for the freedom of some in their desperation and fighting for the suppression of others in their desperation in the same breath. He was totally sincere about Ireland. And totally sincere about slavery.