‘A Farmer’s Son Who Talked Like One’

By Msgr. Francis A. Carbine

A quarter of a century ago, December 10, 1995, Seamus Heaney addressed the international audience attending the Nobel Prize Awards in Stockholm, Sweden. The Poet recalled that, as a boy, he had shared his bedroom wall with a horse. Home was a three-room thatched farmstead.

Heaney further described his “pew straight, bin deep” settle-bed, and mice above the ceiling. ”We lived a kind of den-life between the archaic and the modern.”

In time, however, Seamus journeyed from Mossbawn, County Derry, to Sweden. Along the way, he had scattered his “million tons of light.”

During World War II, the BBC alerted the Heaney family to “world-spasms.” After those years, Ireland not only changed, but much of it was vanishing. Cattle fairs, blacksmiths, and thatchers disappeared. The religious landscape with Fairy Trees, Holy Wells and Station Masses was altered.

Margaret, mother to Seamus and his eight siblings, pumped water from the well both for her family and their thirsty horse. She carried the midday meal to men working on the bog. As a young boy, Seamus helped her in the kitchen: “I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.”

The poet’s father, Patrick, was emotionally reticent. In Margaret’s final minutes, however, “He said more to her / Almost in their life together.” Patrick is given stature in the masterpiece, “Digging”: “By God, the old man could handle a spade/ Just like his old man.”

But Seamus opted for a different life : “Between my finger and my thumb / The squat pen rests / I’ll dig with it.”

In the Nobel Award Speech, the Speaker acknowledged that the “learned poet reveals his Celtic, pre-Christian and Catholic literary heritage.” In fact, Heaney was not a Catholic poet, but a poet who was a Catholic.

Heaney’s six Bogland Poems reach back into the Iron Age with buried victims of ritual killings. These victims, however, anticipate Ireland’s tribal killings in the 20th century.

Four young McMahon brothers, Catholics, were killed in Belfast by English Black and Tans in 1922. Thirteen Protestants were shot by the Provisional IRA, Armagh, 1976.

Peaceful marchers killed by English soldiers in Derry in 1972 verify William Faulkner’s insight: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

The poetry of this Nobel Laureate differs from descriptions of Ireland in tourist brochures. Heaney is “true to the impact of external reality.”

He describes the Great Hunger, 1845: “Wild higgledy skeletons/ Scoured the land in forty-five / Wolfed the blighted root and died.”

When the captain of the “Eliza” encountered a small boat with six starving men in Westport harbor, he responded: “Let the natives prosper by their own exertion.” The “Eliza” sailed away. “World-history and world-sorrow” mused Heaney in Stockholm.

Seamus Heaney is “the voice of a culture which had been silenced for too long.” He did not, however, become radicalized to serve the IRA. Ever fervently Irish, he stated in 1983 : “My passport’s green / No glass of ours was ever raised/ To toast the Queen.”

The Arch-Orangeman, Ian Paisley, called Heaney a “papist propagandist.” Paisley was flagrantly wrong. The Poet described the “bankrupt mythologies” that fueled both the “anti popery” of Northern Orangemen and counter-violence of the IRA.

The Orangemen won the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 and subsequently confiscated Catholic lands in Ulster. These events set in motion a protracted cycle of massacre and counter-attack.

“Servant Boy,” centering on a Catholic lad required to be deferential to “the little barons,” remained “resentful and impenitent.” “Act of Union,” dealing with 1801 merger of Ireland’s government into England’s parliament, “sprouted an obstinate Fifth Column … Conquest was a lie!”

In 1995, Heaney described himself as “steadfast in my non-combatant status.” He endorsed an “agile give-and-take for encountering and contending – like a tennis court – between British and Irish heritages.” Here is gravitas and “ethical depth.”

Heaney received the Nobel Award for poetry embodying “lyrical beauty and ethical depth.” St. Kevin holding the warm eggs of the blackbird, and Leonardo’s sun that never saw its shadow embody unrivalled lyrical beauty.

Seamus’ heart-felt feelings for the accidental death of his brother Christopher, age three-and-a half, are distilled in “Mid Term Break”: “Snow-drops and candles soothed the bedside … His body lay in a four-foot box as in his cot … a foot for very year.” An exquisite elegy!

As a young poet, Heaney read his works to a blind neighbor, Rosie Keenen: “Her eyes were full of open darkness and watery shine.”

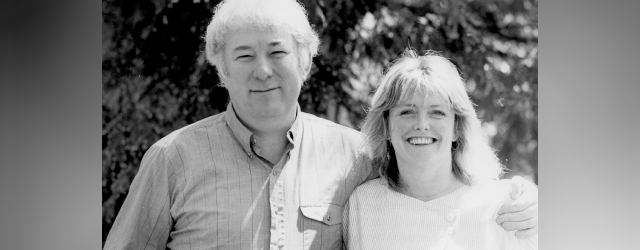

Seamus’ final words to his wife, Marie, were “Noli Timere” – “Do not be afraid.” Minutes later, the Poet died in Dublin on August 30, 2013. He was 74 years of age. He was buried with Christopher in Bellaghy, County Derry.

“Home Place,” the Heaney Center between Derry and Belfast, has been visited by Brian McCaul, Tyrone: “My visit to the Center pleased me personally.”

“I was lured from poem to poem, viewed on ample screens. I suggest a visit also to enjoy the company of the beautiful people whom you will meet.”

Seamus Heaney’s commitment was to the “stability of truth.” While famous for being famous, he remained “a farmer’s son who talked like one.” His tombstone bears the text: “Walk on air against your better judgment.”