By Barbara Nolan

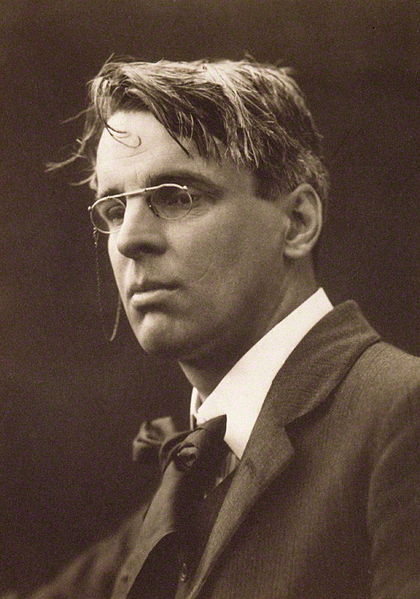

On the 150th anniversary of his birth, let’s pause and admit that William Butler Yeats is not the most sympathetic character to have emerged from the contentious world of Irish letters. In some ways, he is almost a figure of fun: a somewhat gawky young man from an entitled but impoverished Anglo-Irish family who decided to embrace the servants’ culture in a really big way.

He spent a fair amount of time wandering around in the Celtic Twilight (a comforting term, perhaps, for a member of a class that stood to lose a lot in the event of a Celtic dawn), donning Egyptian headdresses in order to achieve spiritual enlightenment in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and at one point getting into some sort of astral fight with none other than the infamous Aleister Crowley.

The fact that he proposed to both Maude Gonne and then, after she rejected him for the last time, to her 22-year-old daughter Iseult, is also kind of funny, as well as disturbing.

There was another side to his character, however, that wasn’t amusing at all. “What is equality? Muck in the yard!” he wrote, in a marching song he meant to be sung by the fascist Blueshirts; and he meant it, even going so far as to argue the India’s vicious caste system had “saved Indian intellect” by preventing the upper classes from breeding with inferiors. He quoted Mussolini with approval.

He might have been a nationalist, but just because he didn’t want to answer to England didn’t mean that he held any ridiculous ideas about the equality of Catholics and Protestants.

About the latter — with whom he identified culturally, although most of his religious beliefs put him outside the pale of most Protestant sects except the Unitarians – he famously said, in the Seanad, “We have created most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence.” His fellow-poet George Russell (AE) got it right when he wrote:

“He has no talent for anything but writing and literature and literary discussion. If I were an autocrat I would give him 20,000 a year, if at the end he had written 200 lines of poetry. If he opened his mouth on business or tried to run any society, I would have him locked up as dangerous to public peace.”

For all his pretentiousness and retrograde political opinions, though, Yeats is still one of Ireland’s greatest poets. Of course there is no rule that great poets need to be good or sensible people — a large number of them famously were not – but, curiously enough, in Yeats’ case it is actually his weaknesses, distilled by the alchemy of poetry, that informed some of his finest work.

He disapproved of both middle-class Catholic demands for equality and physical-force Republicanism, but his aristocratic sensibilities demanded that valor be honored, and his antiquarian interests enabled him to recognize a real-life sacrifice to the goddess Eire. So in “Easter, 1916” he defended not only the fighters whose cause he did not support (We know their dream; enough/To know they dreamed and are dead./And what if excess of love/ Bewildered them till they died?) but also a man he bitterly hated: the “base” IRB member John MacBride. Yeats hated MacBride for marrying Maud Gonne, and also for persuading her to convert to Catholicism, and he had accused MacBride of sexually assaulting Gonne’s ten-year-old daughter. But faced with MacBride’s courage in the face of certain death, and his hurried execution in Kilmainham Gaol, Yeats wrote:

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vain-glorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

If Yeats went around chronicling the folklore of his fellow countryman with a certain amount of condescension, he was nevertheless one of the few among the fin-de-siècle folklore collectors able to bring the old stories to life. Compared to Lady Gregory’s cramped, stilted re-tellings of Irish myths and legends, his “The Unappeasable Host,” is eloquent in its depiction of the children of the old gods:

The Danaan children laugh, in cradles of wrought gold,

And clap their hands together, and half close their eyes,

For they will ride the North when the ger-eagle flies,

With heavy whitening wings, and a heart fallen cold….

And while joining made-up mystical fraternities in the hopes of learning how to put paid to one’s enemies while achieving Nirvana was a common affectation of the late Victorian upper-middle-class, Yeats was serious in his determination to reach something beyond the mundane – and in his poetry he succeeded, perhaps because he never forgot that poetry, in the Western world at least, has its roots in religion and magic.

AE Housman’s test of a true poem, famously invoked by another eccentric Irish poet, Robert Graves, in “The White Goddess,” is whether or not it makes the hairs of one’s chin bristle if one repeats it silently while shaving. If we ignore the fact that about half the poetry-reading public is unable to take that test, we may agree that the sort of physical chill that Houseman was referring to is both rare and magical. Yeats, at his best, can produce that thrill in a way that, say, a Heaney struggles to do: fluidly, musically, with seeming ease.

In the epitaph on his grave in Sligo, Yeats urges us to turn away from remembrance (Cast a cold eye/On life, on death./ Horseman, pass by!). But who, a century or more later, would want to forget the bee-loud glade of Innisfree, the stolen child wandering off to Faery, Crazy Jane, and the beast slouching toward Bethlehem?

In “To Ireland in the Coming Times” Yeats argued for his inclusion in the canon of Irish literature:

Know, that I would accounted be

True brother of a company

That sang, to sweeten Ireland’s wrong,

Ballad and story, rann and song….

These two disparate pleas represent the conundrum Yeats poses for his readers, who may well wish to forget the man, and honor the poet.