By Maurice Fitzpatrick

The global impact of the killing of George Floyd spread to Ireland with protesters asserting that black lives matter in front of the U.S. embassy in Dublin. Similarly, the position of minorities in Ireland has come into far sharper focus since early June — Minister for Culture Josepha Madigan was again criticised in the Dáil for her opposition to Travellers being housed in her community in 2014. The force of the demos since Floyd’s murder has been matched by the force of the debates resulting from it.

The concomitant rethink throughout the world about symbols and statues, and the values that they may represent, has been less prevalent in Ireland even though we are a former colony, a country historically riven by opposing traditions and there is no dearth of contentious symbols.

It is certain that many nationalists would happily remove the statues of men commemorated in Stormont who were historically responsible for disenfranchising the minority in the North of Ireland. One response, espoused in official circles in the North and in Northern Ireland bureaus abroad to the inescapable offence arising from flags, emblems and statuary, is to avoid them. Yet that avoidance strategy cannot be applied by sovereign countries.

Meeting horrific history head-on can more easily happen in museums than in statuary and commemorative edifices. Throughout Eastern Europe today, for example, there are communist museums glorifying the agrarian paradise that virile men and maternal women enjoyed during the altruistic period of collectivism.

The countries that endured the misery of Stalinism and the Soviet Union retain those museums partly because they form an aspect of national memory and heritage. They also keep them because they can be viewed critically and ironically today, and there is an inherent liberation in that.

However, Polish attitudes to Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science, a gargantuan edifice in the capital city centre built by Stalin, are more complex. While its architectural grandeur is undeniable, its connotations of tyranny remain provocative, and many Poles want it demolished. Similarly, the Parliament of Romania in Bucharest, while immense and wondrous in scale and execution, nevertheless represents Nicolae Ceaușescu’s pitiless regime.

Many years ago, I gave a brief tour of a few of the major sites in London to visiting Japanese students. We started in Trafalgar Square and finished off at the Palace of Westminster. At Westminster, viewing the Emmeline Pankhurst Memorial, we discussed the tactics and legacy of the Suffragette Movement. One student was critical of a suffragette, Emily Davison, who died by throwing herself before racehorses at the Epsom Derby in 1913 (in Japan, suicide for a political cause is a highly emotive subject).

The passion, courage and commitment of the British Suffragette movement cannot be denied. Nevertheless, the leader of the movement, Emmeline Pankhurst, was an imperialist who would brook no opposition to Britain’s ‘right’ to control vast swathes of the world and to deprive subjugated nations of their rights.

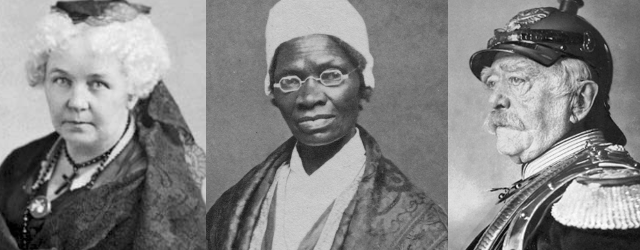

The American incarnation of the same movement, the Suffragists, was led by an avowed racist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Could the suffragette/suffragist movement have happened without elitism and what tends to come with it—access to education, travel, publications and so forth? It most certainly could.

One glance at the founding ideals of the African-American liberation struggle shows that, while educated leaders such as Martin Luther King and James Baldwin were crucial catalysts, elitism had no essential part to play in its ideology. If a movement aims to truly embody a struggle for liberation, elitism is an obstacle rather than an enabler to achieving its goals.

So how do we honour the extraordinary achievements of women’s suffrage movements and yet also acknowledge the injustices they condoned and perpetuated? Both Pankhurst and Stanton are commemorated in statuary in various parts of the world. Later this year, a new statue featuring Stanton will be installed in New York’s Central Park.

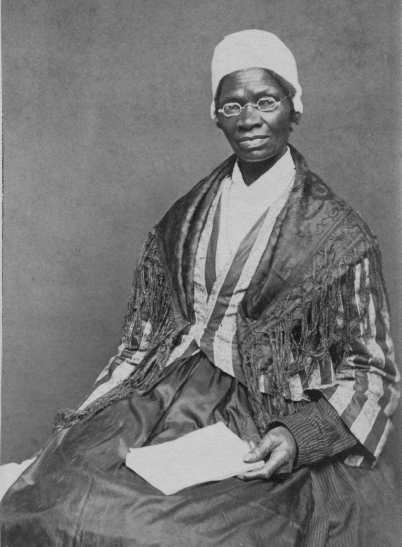

As an afterthought, New York City Public Design Commission approved adding to the plinth a former slave who became a prominent suffragist, Sojourner Truth. That decision has been vindicated in light of the formidable support that the Black Lives Matter movement just gained. Is there something in that decision that may help to negotiate competing historical narratives?

This leads to the occasionally elusive issue of what is intended by a statue. In Germany, for instance, the public history that the government can celebrate is very circumscribed. One historical figure who features in hundreds of plazas and statues around Germany is ‘the Iron Chancellor,’ Otto von Bismarck.

A master of realpolitik, Bismarck was the architect of the unification of Germany in 1871 and he ruled Germany during a generation of relative peace. He is responsible, more than anyone, for the creation of modern Germany, and he is substantially responsible for the creation of the modern nation-state.

That said, do not expect the Poles to dust off statutes of Bismarck that formerly occupied western Polish city centres; do not hold your breath for Namibia, a country Bismarck brutally colonised, to extol his peaceful politics or his democracy. Bismarck stands stolidly on statue plinths in Germany partly because his considerable crimes simply do not compare with those of the Nazi period two generations later — relativism helps to convey his shade with respectability.

Also, the intention behind commemorating Bismarck appears to be to mark his role in forging German statehood rather than to justify (still less heroicise) his crimes.

The intention of a statue can hardly be gleaned merely from the stated aims of the political body that erected it, or the period in which it was erected. It is also known from the meanings imputed to it today. And if the present age cannot see sufficient legitimacy and justice in a statue then we need a dialogue about what it, and the past it represents, means to us now.

Maurice Fitzpatrick is the 2020 Charles A. Heimbold Jr. Chair of Irish Studies at Villanova University.