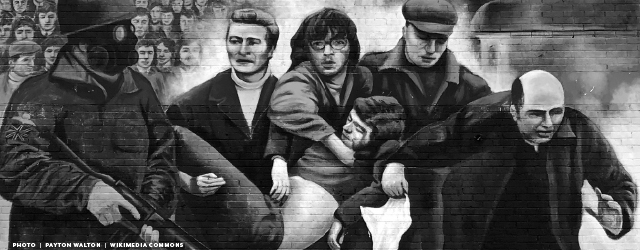

Photo Caption (above): The Bogside Artists Mural in County Derry

By Peter Makem

It was very close to the Kennedy Assassination in terms of memory shock. For all those alive at the time on January 30, 1972, everybody seems to remember exactly where they were when news came in of a mass shooting of civilians in Derry during a Civil Rights march.

I was at an AGM meeting of the Armagh County GAA Board in Armagh City campaigning to get a small club, Lissummon, enrolled in the League when a few people entered the back of the hall and muttered the startling news. I was suiting close to the back and heard it. The news buzzed around the assembled delegates from throughout the county in an ever-loudening buzz until at last the chairman made a statement that “word has just come in from Derry in a newsflash that many people have been shot dead by British soldiers in Derry during a march.”

There was an immediate silence. Then the murmuring began again and the chairman said they should quickly sort out the rest of the essential business of the meeting and all go home.

Almost half a century later it’s all as clear as if it happened yesterday. But as everybody knows, it took that half-century to drag out a formal charging of the guilty even though at the end of the day only one soldier, “Soldier F,” has been charged — with two murders and four attempted murders.

No charges have been brought against any of the other 18 British soldiers involved because, according to the director of public prosecutions, there is not sufficient evidence to secure convictions. The passage of time was cited as a major reason for the decision.

I watched the faces of the relatives of the murdered marchers as they moved into Derry’s Guild Hall to give their own verdict on the verdict of the Director of Prosecutions. After their long desert journey in search of justice, through the infamous Wiggery Tribunal which exonerated the soldiers, through the Saville Report which declared that the marchers were all innocent, through the formal apology from the then UK Prime Minister David Cameron, after all this they looked old, tired but very resolute. There was a sense of utter faithfulness to the memory of their long dead relatives who had been mown down on that far off day, and to the relatives of these who had also passed away since.

Immediate solidarity was expressed at the press conference, that “justice for one was justice for all” but discontent at the huge void regarding the other cases. It was a very emotional spectacle, relative after relative giving their solemn reflections, a blue sky of light at the news of prosecution, but the return of dark clouds that it was so minimal. John Kelly, in many ways the public face of the long campaign, remained stoical that the soldier who killed his younger brother Michael would not be prosecuted.

On TV— and almost superimposed — we watched the photographs of the fresh faces of those shot dead away back in 1972 and the now old, somewhat worn yet immensely dignified faces of the campaigning relatives. At the end of the conference, lawyers for the Bloody Sunday Families announced they have asked for a review of the decision to bring charges against just one former soldier involved in the killings as totally insufficient.

But back in England, there was a hostile reception in military and Tory government quarters. Even a month ago, Secretary of State Karen Bradley made a public fool of herself when she remarked that State killings by soldiers were carried out in “in a dignified and appropriate way while fulfilling their duties.” She has been trying in vain ever since to undo this disastrous utterance. But there are other attempts and calls by military figures create a law of immunity from prosecution – a Statute of Limitation- regarding soldiers who have killed people in the North from the late sixties and end what they term a witch hunt against acting service personnel. This is only to be expected considering their mind-set.

But there is a much bigger picture at stake that has not been remotely answered or even questioned. Who gave the orders for Bloody Sunday? How high up in the then Heath Government was it decided to put the Civil Rights marches off the streets as a follow up to the decision the previous August to reintroduce internment involving the Hooded Men controversy — institutionalized torture of innocent Catholics.

Bloody Sunday was without doubt an attempt to put civil unrest off the streets, and this was carried out in a brutal way by simply firing into the crowd. It was done in Amritsar in India, at Sharpeville in South Africa, Napoleon’s “whiff of grapeshot” and so on. It was part of the old colonial mind-set to settle down the natives. Throughout the Troubles, the parachute regiment — the regiment responsible for Bloody Sunday were renowned for the brutality, provocation and stupidity and they went on the rampage that day in Derry. They were also responsible for the killings in Ballymurphy in a spate of unprovoked violence.

But Bloody Sunday was not a random shooting, something trigger-happy that went wrong. It was a deliberate assault on the marchers, something that was the result of a deliberate order that came down the line and almost certainly was politically inspired from government level. Remember that internment came from a government decision. The following Sunday in Newry, there was a march in protest at what had happened in Derry. I was on that march. But it was the last civil rights/anti-internment march of that era. Bloody Sunday had fulfilled its task of putting civil unrest off the streets.

But in its place came the full campaign of violence that lasted almost a quarter of a century. The British easily adapted to that and were on much safer ground. While in theory they were “keeping the sides apart” in reality they were defending the status quo.

So Bloody Sunday was the great turning point. I am convinced had it been allowed to go on peacefully things would have reached a political conclusion much, much earlier, because once into full blown physical conflict – remember Viet Nam — things get deeper and deeper, more and more brutal and inhuman. It seems that the Derry 13 were the first deliberate victims of a formal British government inspired policy, and the 3,000 deaths that followed, mostly civilian, came out of that vortex. The relatives are among the longest sufferers, ever looking for justice and closure.

But as I may have mentioned before, sadly, closure does not belong to the living.