Photo (above): © Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All Rights Reserved

By Brendan Clay

2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens (dir. J.J. Abrams) ends with the movie’s new Force-wielding protagonist, Rey, tracking down a grizzled, bearded Luke Skywalker living as a hermit on a secluded planet on a secluded rocky island covered in patches of green grass and beehive stone huts.

The planet is called Ach-To, and in The Force Awakens it was played by the island of Skellig Michael, a UNESCO World Heritage Site containing an ancient Christian monastery located off the coast of County Kerry, Ireland.

In the newest Star Wars film, director Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Ach-To and therefore Ireland is the main location for the film’s most important and best storyline.

Star Wars has used exotic locales to portray alien planets before, but this is the first time Ireland has served that purpose, so we’re going to take a look at just how directors J.J. Abrams and Rian Johnson used images of Ireland to tell the Star Wars story:

In a behind-the-scenes video published on the YouTube channel Discover Ireland, Force Awakens supervising location manager Martin Joy says they picked Skellig Michael because “we needed to find somewhere maybe from another time and place.” This serves a motif of the Star Wars saga introduced in the very first film of the series, 1977’s Star Wars, which begins with the famous phrase “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…”

In this spirit, Star Wars uses earth locations that evoke a sense of the old and exotic, which for the American filmmakers has more often than not meant non-American and non-British locations reduced to their most iconic and stereotypical features. The Tunisian desert stands in for the desert planet Tatooine and the ruins of the Mayan city Tikal in Guatemala play the rebel base on the jungle moon Yavin IV.

Cultural signifiers of exoticism also abound. Return of the Jedi portrays gangster slug Jabba the Hutt as a hedonistic, hookah-smoking crime boss with a harem of sex slaves — an obvious orientalist caricature — and Tatooine’s nomadic Tusken Raiders are introduced in 1977’s Star Wars as a blatant riff on real-life Bedouins.

In an article titled “Rogue One smacks of Star Wars’ obsession with aggressive appropriation” on the website Just Add Color, Monique Jones dissects the blunt and blatant use of stereotypical Muslim iconography (sci-fi burkas and hijabs, et al.) and what she dubs the “bazaar aesthetic” in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (dir. Gareth Edwards). These Middle Eastern signifiers are used to represent a Mecca-like holy city in a war-torn conflict zone plagued by extremist rebels-cum-terrorists. Star Wars, more than ever, is willing to blatantly appropriate real culture and use broad stereotypes to build its fictional worlds.

Which brings us back to Ach-To and Ireland. When Rian Johnson took on directorial duties for The Last Jedi, his team built replicas of the Skellig Michael’s distinctive stone beehive huts (known officially as clocháns) on Ceann Sibéal, a headland in Kerry, because shooting on the UNESCO site would have been difficult for the long periods of filming required for The Last Jedi.

As previously reported by Irish Edition, even the brief filming on Skellig Michael for The Force Awakens was controversial, with concerned parties worried about diluting Ireland’s heritage, damaging the historical site, and upsetting the delicate breeding cycle of the island’s seabirds. Moving to a new site avoided the latter two problems, but since the most iconic features of Skellig Michael were recreated in the new location, it still borrows Ireland’s heritage to tell its story. Let’s see what The Last Jedi made out of that heritage:

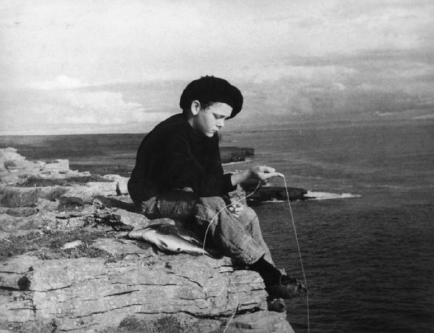

In terms of the lifestyle Luke Skywalker has led during his exile on Ach-To, some of the imagery is reminiscent of Robert Flaherty’s heavily fictionalized 1934 “documentary” Man of Aran. This film features scenes where islanders live a bare, rural lifestyle on the Aran Islands, including a scene where a small boy fishes from the top of a tall cliff. Flaherty’s film is an important touchstone for the sentimental depiction of Ireland that dominated the 20th century.

Luke does not engage in the dire life or death struggle against nature shown in Man of Aran, but his routine has echoes of its rural quaintness, which Johnson filters through a cartoon logic. We find out in The Last Jedi that Luke spends his time marching swiftly around the island, vaulting over chasms, spear fishing from the tops of cliffs, and milking weird sea creatures for green milk.

He lives in one of the clocháns, which in the historical reality of Skellig Michael would have been monastic cells. A convent of matronly and diminutive amphibious aliens — dubbed by Vulture’s Jackson McHenry as “judgemental fish-nuns” — tend to the island.

Johnson gives us nuns and quaint rural seclusion with offbeat, slapstick humor. All in all, it’s a Celtic cartoon, and a pretty funny one at times. But where Johnson really gets some mileage out of the Irish setting is in his reinterpretation of the Force, the mystical energy that binds all life. He leans heavily on the fantasy roleplaying concept of the druidic magic user who is connected to nature, which is a distortion of the historical druids, Ireland’s pre-Christian cultural leaders.

When Rey meditates on the Force, she speaks of it in natural terms instead of invoking the vague battle between the light and the dark of the other films: “The island,” she says, “Life. Death and decay that feeds new life. Warmth. Cold. Peace. Violence.”

Nature imagery accompanies these words. During one part of the film, a force user calls down a lightning bolt straight from the sky rather than shooting it from his hands, manipulating nature directly like no Jedi or Sith has done in a Star Wars movie before.

Utilizing Irish clichés, Rian Johnson expands the meaning and scope of the Star Wars universe on film, and as the film goes on, this evolves into a partial deconstruction of the Star Wars mythology. Unlike Gareth Edward’s employment of modern orientalist trappings in Rogue One that serve to reinforce harmful stereotypes about the Middle East and its residents, the stereotypical Irish motifs in The Last Jedi are delivered with humor and self-awareness and are explored, interrogated, and celebrated.

brendanjamesclay@gmail.com