By Msgr. Francis A. Carbine

The book, The 1916 Irish Rebellion, is a “Triumph.” Published by the University of Notre Dame Press on the centennial of the Rising, this book is a triumph of research, documentation, layout and a prose style that permits readers to assume ”You are there!”

The author, Briona Nic Dhiarmada, and her colleagues have earned both commendation and a wide readership. They invested themselves to produce a companion volume to the Public Television documentary on Ireland, 1916.

Three chapters with subchapters make up the narrative: “Awakening,” “Insurrection,” and “When Myth and History Rhyme.” Instances of subchapters are “That Most Distressful Country” and “Easter Sunday, April 23.”

In 1900, Queen Victoria visited Dublin. In 1911, King George V did the same. They were received with “roars of welcome.” However, beneath the dormant surface, matters were starting to boil.

Maud Gonne, actress and nationalist, denounced Victoria as “the Famine Queen.” In 1911, Gaelic Leaguers objected. A fringe press endorsed cultural nationalism.

Irish theater, Gaelic games, French ideals of equality, and America’s Revolution were forging the spirit of Irish independence. In Yeats’ metaphor, someone was stirring “the boiling pot.”

Historical resentment at 17th century plantations seethed: “The real owners of the soil were removed to make room for cattle.” The Fenian “Proclamation” of 1867 was remembered: “The soil of Ireland belongs to the Irish people, and to us it must be returned.”

Stories centering on Wolfe Tone and patriots of 1798 fueled a new spirit: “Pay them back, woe for woe/ Give them back, blow for blow.”

The early 20th century saw Home Rule and the Ulster Covenant in 1912 as “a circle that would be impossible to square.”

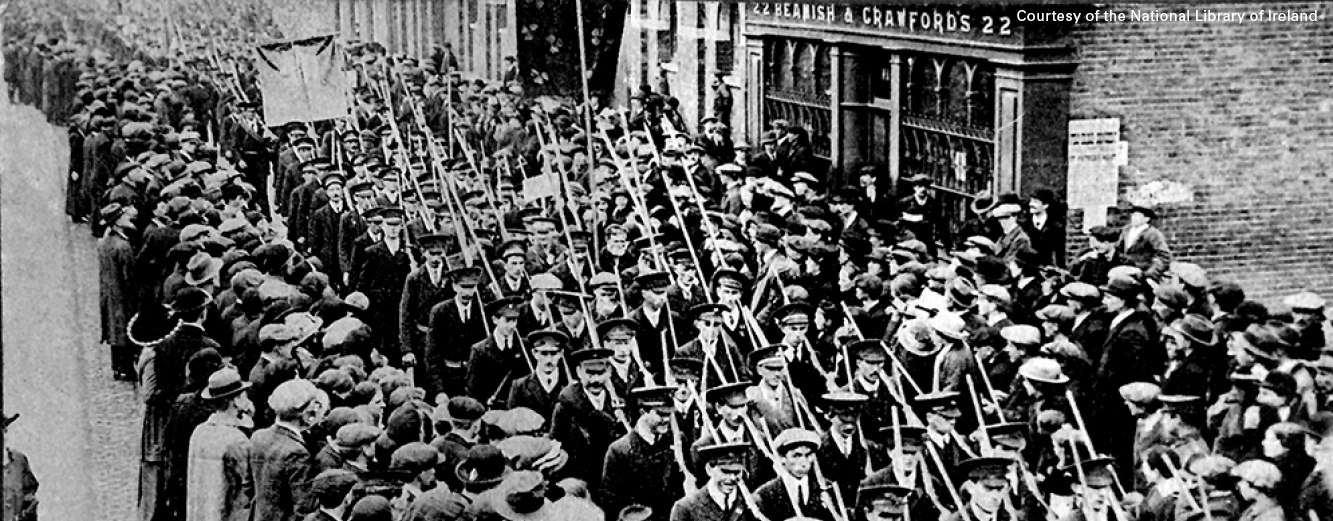

New names flocked to the republican banner: James Connolly, Roger Casement, Alice Milligan, Constance Markievicz, James Larkin, Kathleen Clarke, and hundreds more.

Tom Clarke, executed in 1916, wrote to Joseph McGarrity, an Irishman living in Philadelphia: “The prospect from the national point of view is brighter than it has been in many a long year.” Ireland was now awake!

—

“Insurrection,” the middle chapter, begins on Easter Sunday. April 23, 1916. The chapter provides a daily chronicle. The initial order for Irishmen to mobilize was countermanded on Sunday. Helen Moloney, a radical activist, wrote that it was a day of “confusion, excitement, disappointment.”

—

Monday: The first fatality was James O’Brien, an unarmed policeman.

Monday: The first fatality was James O’Brien, an unarmed policeman.

From steps of the General Post Office (GPO), Pearse proclaimed the new Irish Republic. The Rebels, however, failed to take Dublin Castle, “a citadel of foreign rule for 700 years.”

Tuesday: A member of the GPO garrison noted the “beautiful summerlike day, but not a living thing in sight. Even the birds shun the district.”

Wednesday: On Wednesday evening, an distraught young lady (Grace Gifford) entered Mr. Stoker’s jewelry establishment, Dublin, to buy a wedding ring. She was the fiancée of Mr. Plunkett who was to be shot the following morning.

Thursday: James Connolly wounded. British troops killed 15 unarmed civilians. Priests, “sympathetic to the Rebels,” were in great danger.

Men in the GPO were “soot-stained, steam-scalded, and fire-scorched, sweating, weary and parched.” Everywhere there werered flares, death-white flames, explosions and millions of sparks.

Friday: General Sir John Maxwell arrived as commander-w≠in-chief of all British troops in Ireland. Padraic Pearse was commandant general of Irish Forces. James Connelly praised “the splendid women who have everywhere stood by us.”

Saturday: British terms: Unconditional Surrender!

Sunday: Nurse O’Farrell used an old white apron to fashion a flag of truce.

Monday: All major garrisons surrendered. Leaders were booed by populace. “It seemed like an ignominious end. Time, however, would tell a different story.”

—

Chapter Three – “When Myth and History Collide” – provides statistics on persons arrested, interned, and executed. Padraic Pearse was the first to die. Permitted no defense witnesses, he was shot on May 2, 1916.

Both the husband and brother of Kathleen Clarke – herself a prisoner in Dublin Castle – were shot. Constance Markiewicz had her death sentence commuted to life in penal servitude. General Maxwell described her as “blood-guilty and dangerous.”

Rebels executed in Dublin were buried without coffins in quicklime at Arbour Hill Prison. Maxwell wanted the “sentimental Irish” to have no shrines to martyrs.

The Rising was followed by a guerilla war, treaty, and civil war.

However, the sun would set for the British Empire—first in Ireland, then in Asia, Africa, India, and the rest of the world.

The book utilizes comprehensive resources: paintings, photography, newspapers, diaries, woodcuts, portraits, posters, speeches, witness reports, poetry and song. Details illuminate the “big story” of 1916.

Seamus Heaney: “The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme.”