There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no makers of peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war, at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison, and death in its wake. – Dan Berrigan

By Sabina Clarke

When I first called Father Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest, anti-war activist, teacher, poet and scholar to schedule an interview, he had company and asked me to call him the following morning adding, “If you don’t get me, keep calling because I am worth it.” I squeezed in a question about his close friend and mentor, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, “Father Berrigan, why do you think the Catholic Church hasn’t moved on investigating Thomas Merton for sainthood?” Without missing a beat, he said, “Because they’re afraid of him. He’s too close to the Gospel.” This provided context and some solace to a burning question that has perplexed me for years.

The next day we set up a meeting for the following Friday and for the rest of the week, I wondered, how do you prepare for an interview with a saint? I was stymied. To prepare for someone like this somehow seemed presumptuous; as if what I had to say or ask was really relevant. And that is how I felt. So, in this case, for this interview, I felt stumped.

Dan Berrigan is someone I’ve admired from afar over the years for his public courage and strong political stands. Like many, I saw him primarily as an activist–definitely a radical, someone willing to be arrested and imprisoned for his beliefs; outspoken against the Vietnam war, the Iraq war and war everywhere, a fighter for civil rights and a voice for the poor and oppressed the world over. I knew less about his writing which is prolific and even less about his scholarship which is impressive. He is deeply erudite.

I first saw and heard Dan Berrigan in Norristown in 1980 with his brother Philip on the steps of the Courthouse in Norristown during their trial for the Plowshares Eight. I didn’t see him again until 2001 at a reception at the Wyndham Hotel in Philadelphia with Martin Sheen, where I was introduced to both of them briefly-the priest and the actor-both good friends. They were the joint recipients of the 2001 Solas Award given annually in honor of the late Dennis Clark, the Irish historian and author. The award was presented by The Philadelphia Immigration & Resource Center, now The Welcoming Center. I was struck by Berrigan’s simplicity and spirituality. He struck me as a holy man, in the saint or mystic realm-a true ascetic.

Recently, I’ve thought about Father Berrigan again, especially as he is getting older and about his friendship with Thomas Merton, whose writing I loved and who too, I feel, is also not fully appreciated or embraced by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

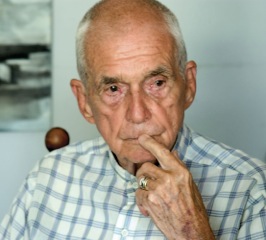

Accompanied by photographer Katharine Gilbert, we stopped at a kosher deli enroute to Father Berrigan’s apartment while our cab waited outside. Twenty minutes early, we arrived at the Jesuit Community House where Father Berrigan lives. I called from the lobby and he answered, ‘Come on right up.’ A plaque on his door had this inscription: a lack of charisma is a fatal flaw. This turned out to be a good omen -for it soon became apparent that this 86 year-old Jesuit lacks neither charisma nor a sense of humor. We exchanged greetings and sat down at his wooden table to share our picnic lunch.

His apartment, awash in sunlight, is homey and inviting and stamped with personality yet tempered with a Spartan-like restraint. The walls are festooned with splashes of color from bright paintings and eclectic wall hangings and personalized mementos reflecting his friends and travels all over the globe. In the tiny foyer is an almost life-size sculpture of the recently beatified to sainthood (in the Catholic Church), Franz Jagerstatter, by the famed Philadelphia woodcut artist Robert McGovern. In this place of honor it would seem that Father Berrigan has an affinity for this man Jagerstatter who was executed for his beliefs and for his refusal to enlist in Hitler’s Nazi Army.

Father Berrigan reminisced about his early life growing up in Minnesota and his family’s move to a farm in Syracuse and about his German immigrant mother and his difficult Irish father and his beloved brother Philip and other important influences in his life: Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and Cesar Chavez. We talked about the writing life and about writers we’ve met and admire–the Irish writer Edna O’Brien and the American writer Mary Gordon. He told his own personal story about Mary Gordon: Mary Gordon was going to some parochial high school in the city and she was getting reproved by a nun for her writing. She wrote to me asking, ‘Can you help me, they are saying I should not be doing these kinds of things.’ I wrote back and said, ‘Full speed ahead. Stay with it. You’ll be terrific.’ She never forgot that.

Father Dan Berrigan | photos © Katharine Gilbert

What was your childhood like?

“We were six boys who endured my father and the Depression-the economic Depression-we were also depressed at times. (laughing) My father was a very tough Irishman. He was also interesting and self-educated, a great reader and a would be poet who got us interested in books at a very young age. I think it was a good start. We lived on a farm in upstate New York having transmogrified from Northern Minnesota, under his inspiration. He couldn’t find any Irish in Minnesota and he couldn’t live without the Irish. So, he persuaded my mother to move east where he knew there was a colony of Tipperary farmers outside of Syracuse. So, we got a farm there.

I read that your mother was German and that at some time your father left the Catholic Church, is that true?

My mother was a German immigrant and the Irish never really accepted her. That was very painful for us as kids and turned us off the Irish. I was years and years getting over that. They were very tribal. My mother was a convert to Catholicism; my father left the Church briefly before I was born but returned. His brother was a priest and his sister, a nun. So, there was a heavy air of Irish Catholicism in the family. We attended parochial school all through high school. When I entered the Jesuits, I was way behind in the quality of education and had quite a time catching up. I had no Greek and not a great deal of Latin and I was meeting the wiz kids from New York City who had plenty of Greek and plenty of Latin and plenty of ego.

What prompted you at the age of eighteen to enter the Jesuits and make this kind of commitment to religious life?

Well, my best friend since the 4th grade, Jack St. George was very interested in becoming a priest. I was listening to him because I liked him and trusted him. We finally reached an agreement toward our senior year that each of us would write to four religious orders and get their literature and exchange the information and come to a conclusion about which one we liked.

We got all this classy stuff from various orders inviting us to ‘come and play tennis with us and swim in our pool’ and so on. The Jesuits were standouts because their little brochure was very unattractive with no pictures and it just talked about years and years of study and teaching. It was very cool and we were both very attracted to it. We thought they must be for real. I had done a lot of reading about the Jesuits but I had never met one. We didn’t have Jesuits then in Syracuse. So, we both applied and we both came in.”

William Stringfellow, a lawyer and theologian, wrote a powerful introduction about you in your book “They Call Us Dead Men” published in 1965. Was he a friend?

He was a very close friend. I met him in Harlem. He was just out of law school and started working among the very poor. Then he wrote a book that made him famous, “My People Is the Enemy.” I was very attracted to this character who was theologically very interesting and who was going to be among the poor and the victimized and the people at the bottom. He and his friend, Anthony Towne were indicted for harboring me when I was underground; that was in a house on Block Island where I took a week off and where I was captured. They dropped the charges against them-it didn’t go anywhere. He was a very loyal and good friend.

Was it your brother Philip who got you involved in the Civil Rights Movement and your anti-war activities?

Yes. He was the closest and most influential person in my life-also Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton and Cesar Chavez. But Phil was number one. Philip and I went to Selma, Alabama and walked with Dr. King and others and watched him preach and were very moved by him. We stayed for about a week. By then, Philip was a Josephite. He worked among the very poor, the black people and all urban poor. He began to draw connections between what was going on in the Civil Rights Movement and what was going on in the war. And he was making connections that I hadn’t even thought of. He would say things like, ‘We would never have dropped the atomic bomb in Europe because it was essentially a racist act. We would only do it against non-white.’ I began to think, ‘whoa, wait a minute.’ Drawing a connection between war abroad and racism at home, I thought, was very profound and very helpful. So, we both started in Civil Rights. I was teaching at Syracuse and he was in New Orleans; so we began exchanging students, north and south. We had white students working with him and we had black students on scholarship at our college in Syracuse-LeMoyne College. So, this worked out well and was very good on both sides. Then, I took a sabbatical for a year and came back after being astonished and paralyzed by the French experience in Indochina. They had been defeated roundly and in effect, gave the war over to us. When I came back, I said to Philip, ‘We better get started against the war or we never will.’

Speaking about his brother Philip Berrigan, a former Josephite priest who died in 2002 at the age of 79, it is obvious from his demeanor and his reverent tone of voice that they were close. Philip, a militant peacemaker, spent years in jail for multiple acts of extreme non-violent resistance. He defied both church and state and was undeterred by either prison or excommunication. He was also instrumental in nurturing the seeds of Dan Berrigan’s anti-war and civil rights activism which came to a peak in 1965 when he was exiled from the United States.

In 1965, you were exiled to Latin America by New York’s Cardinal Spellman, why?

Spellman was obviously never approving of my activities but I don’t think he was the one who sent me out of the country-it was the order (Jesuits). They didn’t want this kind of attention. I spoke at a liturgy at the Catholic Worker after a young Catholic Worker named Roger LaPorte immolated himself in front of the United Nations. Because of this and my anti-war activities, I was sent on indefinite exile to Latin America. There was such a public outcry that the authorities were forced to bring me back. People were asking, ‘What are they doing to this priest? He’s talking against the war, what’s the matter?’ So, I agreed to come back on one condition-that they let me continue my anti-war activities-and they said yes. So, I was brought back and the Kennedys gave me a welcome home dinner-at Hickory Hill, the home of Robert Kennedy. I was invited to supper with Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense and his wife and some other people.

What transpired between you and McNamara at that dinner?

There was an exchange after dinner. The Kennedys are great at holding these kinds of séances. Robert Kennedy asked if the two of us would talk about the war and McNamara said, ‘Maybe Father Berrigan would like to start.’ And I said, ‘Yes…and I’m asking you to stop the war tonight since you didn’t do it this morning’ Well, that kind of stopped him short. (laughing). He said, ‘I’ll put it to Father Berrigan and to all of you; if you come across a people that won’t obey the law, you send the troops in’. I couldn’t believe that I had heard that, because he was equating Vietnam with Mississippi. He sounded like a schoolboy. So, the next day when I got back to New York, I said to a secretary at our magazine, ‘Would you please take down this exchange from last night because in a week, I won’t believe I heard it.’ And McNamara was considered to be among the very brightest and he sounded like a schoolboy.

During your trial for the Catonsville Nine action, there was little support for you from the Catholic hierarchy or from Catholics anywhere, for that matter. Why was that?

There may have been a few but I can’t think of anybody outstanding. This was all so new and the clericism was all so entrenched-even sacramental clericism which specified where you should be and where you shouldn’t be. You belonged in the confessional or at the communion rail at the altar but you didn’t belong on the picket line. I said to Philip, ‘We are going to have a very tough time in front of Catholic audiences’ which proved to be very true. This has changed.

How do you explain your willingness to go to prison for your beliefs?

Philip and I were out there two years before we were locked up. We always realized that part of our job was facing people publicly along with writing and witnessing.

When did you first meet Thomas Merton?

I first started corresponding with him around 1960. He had written an article in the Catholic Worker about nuclear war. It was devastating-an incredible piece of work. I wrote to him and he wrote right back and said, ‘come on down, let’s talk,’ So, I went to Gethsemani (Abbey in Kentucky) once a year from 1960 to 1968. And we would spend several days together-sometimes with the community, sometimes with outsiders, sometimes one to one. The chemistry was good. We got to be very close.

After your participation in the Catonsville Nine action in 1968, Merton distanced himself from you somewhat. How did you feel about that?

Yes, that was very painful and puzzling to me because I had no access to him. After that we never had the kind of access we had had. Then he left for the East; he was off to Bangkok and then he was dead. He was gone and he was dead. So, it took me a long time to get over his death and it was many years later that I could even speak about him in public. Shortly before his death, Merton wrote, ‘I now realize what my friends were doing at Catonsville and I am wondering how long a monk can continue to keep the law.’ So, when I came across that, it was a great help.

What was your take on September 11th?

Let me tell you a little story about the morning of 9/11. I was at the computer, as usual, and a friend of mine called from North Carolina. He was shouting into the phone, ‘What in God’s name is going on up there?’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘A plane has just flown into one of the towers downtown.’ Without thinking, I said, ‘So, it has come home at last.’ We had been asking for that for years and years.

Do you think our government had anything to do with it?

Well, the work remains the same whether they knew about it or not. I don’t think any of them would have any moral boundaries about what they would do. They were aching for revenge and they got us into a bottomless pit.

In 1996, on the occasion of Dan Berrigan’s seventy-fifth birthday, his brother Philip Berrigan wrote:

“Who is my brother Dan Berrigan? Very simply, Dan Berrigan is what Dan Berrigan has done, is doing, does. According to Gandhi, conduct is the best yardstick of a person’s life. Dan’s identity is the excellence of his life. He is one of those remarkable people who has narrowed the gap between word and deed, who has put flesh on his words.”