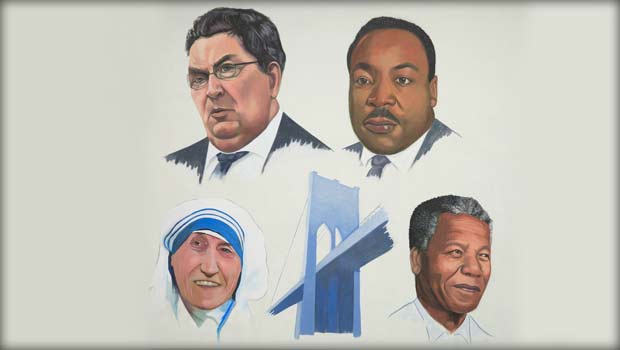

Caption (above): On one of their famous murals, the Bogside Artists of Derry honor four Nobel Laureates —John Hume, Dr. Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela. All were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. For information, visit www.bogsideartists.com

By Maurice Fitzpatrick

Crossing a bridge in a time of high political tension can be a metaphor for transformative political change. Just as members of the American Civil Rights Movement’s holding firm on their right to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in their Selma-Montgomery march was a watershed moment for that movement, so too was the attack on non-violent civil rights marchers as they crossed Craigavon Bridge in Derry City by the Royal Ulster Constabulary on October 5th, 1968 in the history of our island. It was the beginning of the end of the Northern Irish State.

Similarly, too, in January 1969, in homage to the Alabama march, a group of civil rights marchers in Northern Ireland, mainly students under the banner of the People’s Democracy, organized their own version of Selma to Montgomery: a Belfast to Derry march. The Northern Irish Civil Rights seekers were attacked en route, most savagely at Burntollet Bridge, just outside Derry, having conducted themselves peacefully all the way from Belfast.

The outrages at Burntollet, and at Craigavon a few months earlier, exposed the extreme violence of the State to television viewers and newspaper readers outside the Northern Irish State, who rallied to the support of a people whose non-violent demonstrations defeated the state’s sole weapon, the jackboot. Much the same publicity victory as back in Selma.

Selma, a film released earlier this year, is an attempt to re-create the drama that surrounded that city in 1965. It shows that President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s alignment with the civil rights campaign was a crucial catalyst for reform, and the US President’s insistence on triangulating the issue was a devastating blow to white supremacy. As LBJ put it, “In Selma . . . many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed . . . There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is only an American problem.”

The film excels in its vivid depiction of brutality. LBJ knew very well the emotive power that non-violent protest could have when met by recalcitrant statist aggression; non-violent protest played well on television, because it swung public opinion in favour of the demonstrators like little else could. As LBJ put it, “Pretty soon, the fellow that didn’t do anything but follow . . . he’ll say, ‘Well that’s not right, that’s not fair.’”

Violence, which film audiences may think themselves immune by its pervasiveness in cinema, is hugely unsettling in this film, something achieved through the authentic portrayal of attacks on innocent people and in the exactitude of the human suffering. As soon as the battle charge comes from mounted policemen against marchers on their first attempt to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the crowd disperses in chaos. The cattle prods, the billy rods, the horse-whips wielded against the marchers is startlingly well captured.

Back in Northern Ireland, civil rights campaigners faced comparably sinister members of police (the RUC colluded in the Burntollet attack) and members of government too: as unionist politician, William Craig, stated to a cheering audience, “when the politicians fail us it may be our job to liquidate the enemy.”

In Selma, the initial tactic of LBJ in his negotiations with Dr. Martin Luther King is to procrastinate. LBJ insists that the issue of voter registration in the South and its corrupt administration was one of the myriad concerns of the White House (the veracity of how this disagreement between King and LBJ as shown in the film, has been contested by historians and Andrew Young, King’s deputy). Implacable, King refuses to allow Johnson to buy time.

Selma does not give full scope to LBJ’s political acuity, and that is unfortunate. Film scripts have created simplistic conflicts between lead characters: the noble person faces the dastardly capitalist; the reactionary puts obstacles in the way of the heroic modernizer. But King and LBJ had much in common, more than this film suggests — their reading of the situation in the South being a good example of their common ground.

Like Northern Irish Civil Rights leader John Hume, King knew very well how to force the government’s hand when he wished. King, exiting jail in Selma, declared that he was on his way to see LBJ, realizing that that comment to the media guaranteed his entry into the Oval Office — LBJ wanted to avoid scenes outside the White House of the magnitude that his predecessor, JFK, had to face. Selma adroitly weaves between the streets of the South and the Oval Office.

Both Selma and Derry were the sites of cataclysmic events that propelled an entire transformation of the political landscape of their countries. Bloody Sunday in Selma, on March 7th, 1965, caused a huge expression of public sympathy in the US, and it was ultimately an unstoppable advance for the Civil Rights Movement towards gaining the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After Bloody Sunday in Derry on January 30th, 1972, Northern Ireland’s parliament in Belfast fell within a few months, establishing direct rule of Northern Ireland from London.

Selma implies that King did not lead the first Selma march due to a family crisis. Hume did not march on Bloody Sunday in Derry because on the previous Saturday, January 22nd, he had led an anti-internment march on Magilligan Beach, just outside Derry, at which the British army disgraced itself by opening fire with rubber bullets on women and children who marched into “a prohibited area.” With conditions so volatile, Hume urged other Civil Rights marchers not to march the following week on the streets of Derry; when they did not heed his instructions, the British army fired live rounds on protesters and murdered fourteen people.

The continued role of John Lewis, played in Selma by James Stephens, is also important. Film audiences in the US, in particular, will know that Lewis went on to have a long career in US Congress.

In April 2014, Congressman Lewis walked across Derry’s Peace Bridge — a bridge that runs parallel to Craigavon Bridge — where he was greeted by the mayor of the city and John Hume. Given that Lewis also leads an annual walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge into Selma, the symmetry of the occasion was remarkable. Lewis also saw the Dr. King and John Hume mural in Derry’s Bogside area.

Out of these sites of anguish and schism come peace commemorations, peace bridges and high calibre film productions. As the half-century anniversary of the Craigavon and Burntollet attacks approaches, another symmetry, a film on the Belfast-Derry march, is in order.