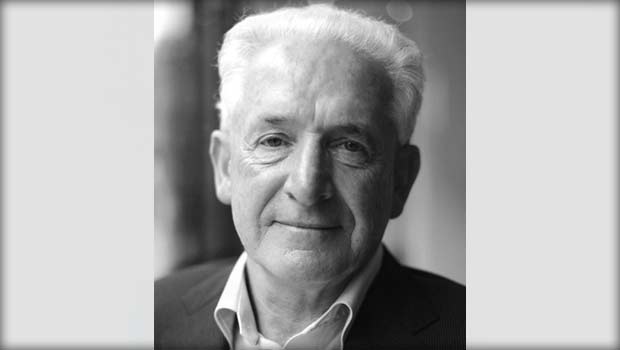

By Barbara Nolan

For a heretic, Father Anthony Flannery is remarkably down-to-earth.

The 67-year-old Redemptorist priest, a native of County Galway, has a sharp wit honed during a long career as an itinerant preacher and a highly developed sense of humor.

“It’s important in the Church that you’re able to laugh,” he says. So it’s hard to remember that he’s currently in danger of excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church and therefore, according to its doctrines, at increased risk of damnation.

“It’s important in the Church that you’re able to laugh,” he says. So it’s hard to remember that he’s currently in danger of excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church and therefore, according to its doctrines, at increased risk of damnation.

Flannery himself professes to be surprised that anyone in Rome is even interested in what he has to say. “I suppose I’d been a bit outspoken,” he said, but, as he puts it, he’s on a “tiny little island on the outskirts of Europe and the Atlantic…Who gives a damn what I’m saying in the Vatican?”

Quite a few people, as it turns out, including Cardinal Levada, former head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (formerly the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition. Yes, that Inquisition.). In fact, Levada was interested enough to compare Flannery to the most famous heretic of all. “If you hold these positions you are formally in heresy. For Martin Luther, or the Protestant reformers, they were key issues and they denied these doctrines of the Church.”

On a recent evening at the University of the Sciences in West Philadelphia Flannery spoke about how a lifelong Redemptorist, who joined the order 50 years ago and spent much of his life as a travelling missionary, found himself stripped of the right to perform the Mass and defending a charge of heresy instead of celebrating his jubilee.

The talk itself, sponsored by a number of progressive Catholic organizations, was an act of defiance, since he has been ordered by church officials to keep silent. Flannery scoffed at this ban, and joked about it. “Before I get on to papal infallibility, hands up, the Vatican spy!”

Just what is the fuss all about? Considering that practicing pedophiles within the Church escaped punishment for decades, that Robert Mugabe, the Catholic President of Zimbabwe, routinely tortures and murders his political opponents but is welcome at events in the Holy City, one has to wonder: what exactly does it take to draw the wrath of the Vatican these days?

Well, Flannery’s position on the role of women in the Church doesn’t help: he does support ordination, although he thinks it’s more important right now to have “a different understanding of the ministry in the Church” rather than to push for female priests. His views on sexuality won’t win him many Vatican friends: “Catholic sexual teaching is very deficient, and in some ways very damaging…the ban on artificial contraception is wrong.”

And his defense of priestly marriage has got to be an irritant, although in this case, he’s not suggesting an innovation: priests in the Roman Catholic Church were able to be married under canon law until 1139.

But, controversial though they might be, these views weren’t what stuck in the craw of the old Inquisition. When the Superior General of the Redemptorists first summoned Flannery to discuss the charges against him, it turned out that the big charges were a little more esoteric.

Specifically, he was charged with denying that Jesus instituted the priesthood in its present form, or the church itself, for that matter. These are charges that Flannery cheerfully accepts.

He believes that the priesthood evolved throughout the first hundred and fifty years A.D., and he pointed out that he was writing in the context of the child sex abuse scandals when he said that “the priesthood, as we have it today…the church, as we have it today, is not what Jesus intended.” It seems like it would be hard to argue with that.

The Congregation does want to argue, though, since a literal interpretation of that idea might knock the underpinning right out from underneath the Church. And Flannery says he doesn’t dispute the right of the Vatican to correct him, particularly since, as he pointed out, “I’m not an academic theologian. I was a populist preacher and popular writer.”

But he wonders why his unorthodox ideas have loomed large enough to obscure 50 years of service to the church: “I don’t imagine that any of you lie awake at night worrying about these things, and neither do I,” he says.

When he tried this kind of logic out on the Congregation, however, they just upped the ante: he was ordered by the new Prefect, Gerhard Müller, to sign a statement declaring that women could never, ever be priests, and that traditional Catholic sexual teachings were correct in their entirety.

This, Flannery says, was the breaking point for him. “I wasn’t going to lose my life over whether Jesus ordained those twelve apostles.” But the statement was something else again. “Everyone would have known I didn’t mean it — my credibility would be shot,” he said. “How could I look in the mirror for the rest of my life?”

There’s no doubt that Flannery is deeply upset by the way the Vatican handled the situation. He says he doesn’t understand why, instead of being questioned by the Congregation about his suspect writings (which were published in a Redemptorist magazine), he first became aware that there was a problem when his Superior General summoned him and handed him two pieces of paper from the Congregation, one listing his objectionable writings and the other listing the consequences he would face should he fail to renounce them. He says was not asked to clarify his writings nor given an opportunity to defend himself. “It was totally unjust.”

As the situation escalated, he was put under a formal precept of obedience not to attend the annual meeting of the Association of Catholic Priests, but “I went because at that stage I thought the whole thing had become ridiculous,” he said with deep disgust. In an earlier part of his U.S. tour, he was asked how he could so blithely set aside his sworn oath of obedience by disobeying the orders of a legitimate authority.

Flannery said that the question gave him a moment of clarity. “The keyword is legitimate. Any authority that tramples on the dignity of a human being has long ago lost the right to be considered a legitimate authority.” And by trying, convicting, and sentencing him before he was even aware that there charges against him, Flannery feels, the Congregation did just that.

Strong words, indeed, but will they will make any kind of an impression in the Vatican? Flannery calls himself “a child of the Second Vatican Council” and argues that the Church is paying less attention than it ought to the sensus fidelium, which the Catechism defines as the “supernatural appreciation of faith on the part of the whole people, when, from the bishops to the last of the faithful, they manifest a universal consent in matters of faith and morals.” “By listening to the voices of the people respectfully and with discernment, decisions can be arrived at which everyone can live with,” Flannery argued.

Well, maybe, although it’s not clear that the Congregation is interested in Quakerish consensus. Condemnation has traditionally been rather more in their line, though Flannery says that the recent Extraordinary Synod on the Family has made him hopeful that things may be changing in the Vatican.

“Francis is showing himself to be tough as nails,” Flannery said. “His vision is the vision of the Second Vatican Council, and I didn’t think I would ever live to see that restored…The Synod was a major success because of the way it was conducted. People could speak their minds freely and without fear.”

Flannery feels that, had the Church adopted the habit of listening centuries ago, we might have had a world without the Reformation: “Imagine if the Church had listened to Martin Luther and Calvin, and brought in their good ideas…but they had lost the ability to listen.”

Whether or not the Church is listening to him, most of the audience was, with rapt attention. “You are so abnormal,” one lady said to him with obvious admiration. “You’re like a mutation. I hope the mutation is picked up by other people and the fear factor is mollified.”

Flannery had hopes that it will be: “I just don’t know. It’s going to be a hell of a struggle, but I don’t think the convinced conservatives are that large in number.” Bishops chosen, he argued, for their docility “will go whichever way the wind is blowing.”

In the meantime, he said, to go public with his story is “the best thing to do for the Church I loved and continue to love.”