[editor’s note] We congratulate Tim McGrath for writing an outstanding and long-overdue book on the heroic life John Barry. Though born and raised in Wexford until the age of 15, Barry quickly adopted America as his country for which he fought valiantly in its cause for freedom from Britain. Philadelphia became his new home and provided his final resting place in the graveyard of Old St. Mary’s.

Tim McGrath is a third generation US born Irish-American and president of the Health and Science Center, a Philadelphia based executive search firm. An avid sailor with published articles on health care and naval history, John Barry is his first book.

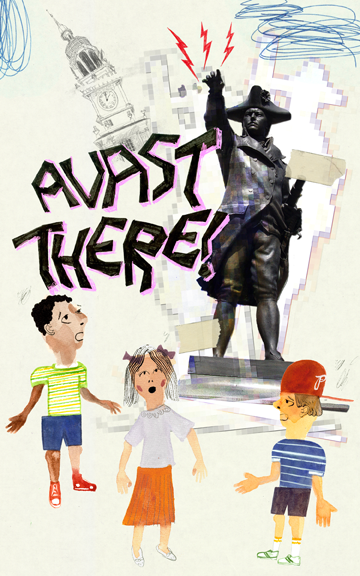

The illustration is from "Travels with the Commodore; or How John Barry's Statue Taught Us Some History" as told to Tim McGrath, author of "John Barry "and illustrated by his son, Ted McGrath

Q. Why did you write the biography

A. Like most Irish-Americans from Philadelphia, I was introduced to John Barry’s statue at a young age. My father first took me to Independence Hall when I was four or five years old. I asked him what the statue was pointing to. Instead of saying “he’s pointing at the enemy ships” or down the path of the Delaware River, he replied, “He’s pointing to where he is buried” — then took me over to the cemetery behind St. Mary’s on Fourth and Locust! So I got to make my first trip to a graveyard and see Independence Hall on the same day.

I actually wrote the book on a bit of a dare. I’d been reviewing the Barry-Hayes Papers at the Independence Seaport Museum and other documents of and about Barry at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the American Philosophical Society here in Philadelphia and contacted Jim Hilty, a terrific professor of history I’d studied under at Temple University. I mentioned Barry’s remarkable story and suggested that a grad student or professor could make quite a book out of it, and he suggested I do it. In subsequent conversations he laid out the way to go about it and nudged me further and further down the path.

Q. Were there previous biographies available

A. There are several, but the most recent one was published in 1938 and long out of print. It was written by William Bell Clark, who spent most of his life researching and writing books about the early days of the Continental and United States Navies.

Q. Where did you find information on Barry and was it hard tracking this down

A. In January of 2003 I reached out to Megan Fraser, then librarian at Independence Seaport Museum, and requested time to visit the museum library to read the out of print books. She informed me that the museum had Barry’s family papers, and after that initial visit I was hooked. The more I read the more I realized that a truly great man was being forgotten.

Other Barry logs, letters, and documents are found at the Library of Congress, the New York Historical Society, The FDR Library, the New York Public Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the Early History Branch of the Washington Navy Yard, among others. Haverford College has several of the wonderful letters between Barry and his second wife, Sarah Austin.

The Barry-Hayes Papers are now available online, thanks to the efforts of Matt Herbison at Independence Seaport Museum, the staff at the Villanova University Library, and Russ Wylie, who’s well known in Irish-American circles for countless projects. The link’s available on the Seaport Museum web page.

Q. In the course of your research and writing, did you discover any new information on Barry

A. Mr. Clark’s book is very thorough—he really is the Homer of the American Navy—and reflective of the times in which he wrote it. There were a couple of things we uncovered, or at least dealt with more fully. Barry’s in-laws, the Austins, were a very successful family, running the Arch Street Ferry; they had their own pew at Christ Church. They were ripped in two by the Revolutionary War. The younger brother, Isaac, went with Barry to fight with Washington at Trenton and Princeton, while William, the eldest, fought in a Loyalist regiment.

The second draft of the manuscript was nearly done when Kathie Ludwig, librarian at the David Library of the American Revolution at Washington’s Crossing, unearthed documents showing that William later commanded a twenty-gun ship for Benedict Arnold’s raids into Virginia and was later captured at Yorktown! After the war William lived in Nova Scotia, England, and later in the Carolinas. Ironically, while his own brother and sister (Barry’s wife) cut him off, Barry maintained a warm correspondence with him, addressing William as “My Dear Brother.”

For me the most ironic fact in Barry’s life was that this refugee from the Penal Laws in Ireland later owned slaves. His best friend in his later years was also his physician, Benjamin Rush, who by that time had freed his own slaves and become one of Philadelphia’s most fervent abolitionists. They must have had some interesting conversations on that subject.

Q. Did Barry view himself as Irishman, Irish-American, or just a sailor?

A. To his credit, he never forgot where he came from, but he really saw himself as an American. In several of his letters to old acquaintances in Ireland or friends in the West Indies he calls the United States “the finest place to live on earth.” He also loved his adopted city and state; when a boyhood friend writes from Ireland that he’s thinking of settling in the Mohawk Valley in New York, Barry tries everything to talk him out of it, including dire warnings of bitter winters, barely sheltered in a forlorn, drafty “log house.” He closes with a demanding that he come to Pennsylvania.

As a sailor, his skills were unsurpassed. His capabilities were admired by foc’sle hand and officer alike. And he used his talents in his steady rise to the top of his profession before the Revolution, with command of the Black Prince — the finest American-made ship before the war — visible proof of the regard merchants had for his maritime and leadership skills.

Q. Did Barry retain contacts with Ireland?

A. He certainly did. Barry constantly sent money to his parents and other relatives, who not only depended on his generosity but came to expect it. He could be a “soft touch” for any relative in need. Quite often young Irish emigrants showed up at his doorstep, and he did what he could to find them work.

When his sister and brother-in-law died, he sent for her children to come live with him. One, Patrick Hayes, became an excellent mariner in his own right, and was his uncle’s pride and joy. Barry had no children, and Patrick became the son he never had.

Q. What was part of his life or career did you find interesting and why?

A. Of everything I learned about Barry, the most interesting was his voyage to China, made after the Revolution. He took his nephew Patrick, then seventeen, along. The boy kept a fascinating journal on the outward voyage, full of a youngster’s wide-eyed reactions to the ports of call, storms at sea, and encounters with Africans, Asians, bats with a seven-foot wingspan — it’s quite a read.

Barry’s own recollections of his stay in Canton are both methodical and humorous, especially his abysmal failure as a shopper for Philadelphia’s upper crust citizenry, who contract Barry to buy silks, and other goods — particularly one Mrs. Hazelhurst, who expects Barry to buy all of China’s china with fifty dollars. He also is struck hard by the disparity of unbelievable wealth seen on a mandarin barge, sailing next to the most abject poverty he ever saw on countless sampans.

Prior to this voyage Barry attended the Pennsylvania Assembly’s debates over the new Constitution. When the opponents in that body declined to show up and deny its supporters a quorum, Barry led a gang of wharf toughs down Chestnut Street and shanghaied a couple of reluctant pols back to the State House (Independence Hall) and their duty. It would have been a great scene in a John Ford film.

Q. What part of his life or career was most important for the history of our nation?

A. While his Revolutionary War exploits rival anything found in the Hornblower or Aubrey-Maturin novels, I think his most important contribution came with the beginning of the United States Navy, during the Quasi-War with France. While Barry is senior captain, his best days are long behind him, and he’s forever beset by his annoyed bosses: President John Adams and Navy Secretary Benjamin Stoddert. Nonetheless, while his military successes are dwarfed by those of his friend Thomas Truxton, Barry serves admirably as a “Mr. Chips” to the next generation of naval heroes: Stephen Decatur, Richard Somers, and Charles Stewart among them. His skills in this regard don’t go unnoticed; Stoddert sends his own son to Barry, to be taken under the commodore’s wing.

Barry’s story is a truly remarkable one. Discovering it and telling it has been a real privilege.