By Charlie Reilly

Almost everyone knows Eugene O’Donnell as the Minor-, twice-Junior, thrice-Senior All Ireland Dancing Champion of Ulster, and in his final competition Senior Champion of All Ireland. As the Derry Journal reported, “He has held every available award for Irish dancing, a record that may never be repeated.” To this day, residents of Derry City recall his extraordinary skills on the pitch as a striker, and many still talk about him as a child prodigy who played traditional Irish music on the BBC at age 13 and classical music the following year in England and France.

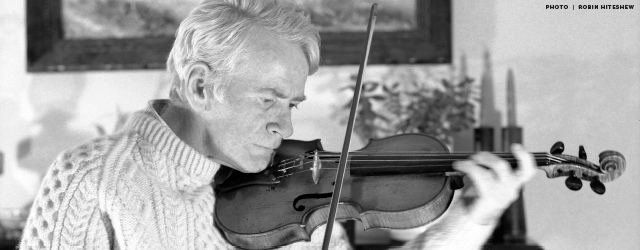

Residents of the greater Philadelphia area recognize Eugene as a founder and teacher of the Philadelphia Ceili Group and, of course, as an internationally acclaimed fiddler who with Mick Moloney performed at such universities as Penn and Harvard; at the Smithsonian where he played his first Stradivarius; and at Hazard Kentucky where the mayor proclaimed him an official Duke.

And everyone who has been around Eugene for a few hours or beers knows of his passionate love for Derry City and his decades of remorse over leaving it at age 25. Given his extraordinary successes in Europe, you might wonder why he left in the first place and why he waited decades to move back. The story is a complicated one and it’s a subject he rarely spoke about. A quarter century ago he told me about it, but did so with the admonition that I was not to publish his memories until he had passed away. Eugene O’Donnell died on June 28th.

Popular imagination recalls The Troubles as occurring during the years before and after the Partition and recurring in the 1970s and 1980s. But during the 1950s the country was riven by violence and by the ferocious steps Britain took to maintain control of its “other island.“ In 1957, the year of Eugene’s departure, the passing of the Civil Authorities/Special Powers Act resulted in the arrest of over 100 Irish Republican suspects in Northern Ireland alone. That same year saw the early days of the IRA’s Border Campaign (1956-62), the first sustained guerilla movement since the 1940s.

Today it’s particularly remembered for the death of Sean South of Garryowen in a raid on the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Fermanagh.

Such events hardly went unnoticed by the O’Donnell family, especially by its musical prodigy who was enjoying enormous popularity for his musicianship and was paying the bills as a professional draughtsman, and who . . . But let Eugene tell the story in his own words.

“It was 1957. I was 25 years old and working by day in an architectural office and playing the fiddle on nights and weekends, and there came a time when I was approached at a ceili in the Criterion Ballroom in Derry City by a family member and a guy I’ll call Michael Plunket. They knew I was working as a draughtsman and it turned out they wanted me to make an application for a position with the Architectural Division of Her Majesty’s Service in Derry City. They couldn’t give a damn about Her Majesty’s Service but they did give a damn about any plans and secret documents I might have access to. As you might have guessed, both were officers commanding the IRA in Derry.

“I made the application and was interviewed by an Englishman named Coleman. He started by asking about my career as a football player and then asked if I played cricket. I lied and said of course I did. He got very excited. He knew I was a violinist with the Land of Coppolo Orchestra and then out of nowhere this Coleman says, ‘Oh, you don’t need a job here, I can get you a terrific job in the head office in Bath in England.’

He jumps on the phone and talks to some big shot in Bath and tells him ‘I’ve got him! He’s a superb violinist and an excellent football player to boot. He would be perfect for the Bath Symphony Orchestra.’

“God help me, that was the last thing I wanted so I said, ‘Look I’m not going to Bath, I want to stay right here.’ He said, ‘But I’m telling you, if you go to the head office in Bath, your promotions will flow like buttermilk.’ I told him ‘I don’t give a damn about buttermilk, I’m not going to Bath, forget it.’ He couldn’t believe me and he certainly wouldn’t believe me if I told him the truth that I was not interested in promotions.

What I was interested in was working in Her Majesty’s Architectural Office in Derry because they were the ones who got all the printing plans for the Admiralty, which was the government department responsible for the command of the Royal Navy. As you can imagine, the IRA were very interested in those plans.

“So I got the job in Derry and started to collect documents. The IRA were especially interested in the topography of a place that had a number of oil tanks because they needed to know where the oil might run if the tanks should somehow be blown up. I carried so many plans out of there. I used to tear them up and hide them in my shoes because you were liable to search leaving the base. Michael was on the run at the time but he was still in Derry and the plans I carried out were all stored in the local Boxing Club.

“One evening I was playing at a ceili in the Ritz ballroom, and a fellow named Reds calls me down off the stage and says ‘They’ve raided the Boxing Club and found all of the documents and plans you took out. You’ve got to get across the border tonight. Your life hangs in the balance. It’s a matter of treason. You’ll be hanged.’

“Very few in Derry knew about this. I went home and told my father and mother, who had no idea I had been working with the IRA — though they would have approved. I couldn’t sleep that night. Any knock on the front door would have sent me out the back door. I had a few coins in the bank which I withdrew the next morning, which was April first, and I fled to Donegal.

“It broke my heart. I was 25 miles from Derry City but in another country and I couldn’t go back home. I thought, I’ll go to America and become a citizen there and when things quiet down I’ll get back. I was homesick for years! Odd though it sounds now, the reason I became a citizen of America was so I could get back to Derry.

“After I became a citizen and, quietly, returned to visit, I was sorry to see nothing had changed. At first I stayed in Donegal and while there I learned I had become a suspicious person. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) got wind of me but there wasn’t much they could do because Michael and my relative kept their mouths shut — and spent years in prison for their trouble. The RUC put the word out that I was armed and dangerous and should be watched carefully. The word reached a superintendent named Kelly in Donegal, who happened to be a good friend of a cousin of mine, so he told me right away what was going on and told me to keep a low profile. A low profile! Here we have the RUC and the Garda on alert for someone in possession of a violin.

“On my visits home I was followed. They had a detective right across the street and it seemed no matter where I went somebody was behind me. I was still able to perform, and I remember when this City Council guy whose name I can’t recall — he was a Protestant fellow who played the banjo — sought me out to say he was very much interested in Irish music and would love to come up and hear me play. He did, and after the seisiun he said he would be happy to drive me home. I said it might be better if you didn’t because there’s a detective watching the house. He says don’t worry about that, and he drove down Glasgow Terrace.

“So we’re sitting in the car gabbing and within minutes up comes the detective to write out a summons on the car. He recognized that it was a government car, decided he had seen it under suspicious circumstances, and decided the driver was consorting with me. I felt awful and told my new friend I was worried that something like this might happen. But the government guy said, ‘Well the laugh’s on him because I left my own car in the garage and took the first work car I found. Nobody in the garage knows I took this one and no one cares.’ The government guy went on to say ‘With any luck your detective will put the finger on some big shot and wind up getting himself in trouble.

“I’ll never regret my years in America, but my heart never really left Ireland. The IRA experience is a part of my life that I rarely talk about. I don’t consider myself a great patriot, but I do consider myself an Irishman. It was 1957, and I was trying to hold onto part of my country. Every ardent Irishman felt that way.”

Charlie Reilly is professor emeritus at Montgomery County Community College. He just finished his fourth book, How They Write.