By John Rossi

From the late nineteenth century until World War II ethnic humor and downright slurs, often good humored but also humiliating and insulting, were commonplace in American literature. Ethnic and racial stereotypes proliferated: Gallagher and Shean, Amos and Andy, Life with Luigi, Charlie Chan. Even a classic comedy act like the Marx Brothers was built around ethnic stereotypes. Chico was the dumb Italian, Harpo the country bumpkin while Groucho was the classic Jewish con artist.

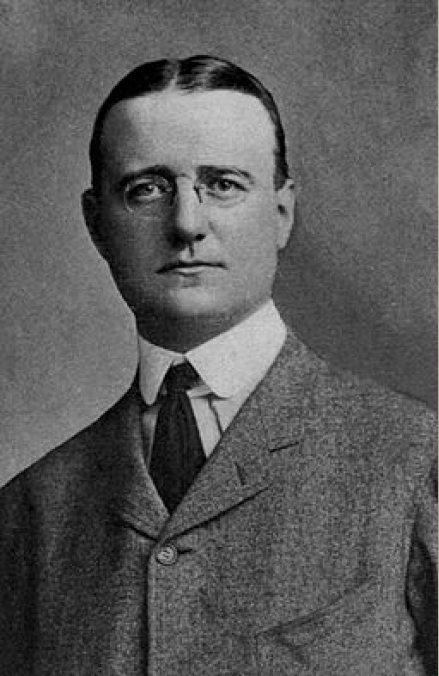

During these years, no one handled the role of the ethnic commentator with greater imagination better than Finley Peter Dunne through his creation, the Chicago Irish bartender, Mr. Martin Dooley.

‘Mr. Dooley’ was one of the first and one of the shrewdest at the use of an ethnic stereotype but not just to garner laughs but also to make a serious point. Dunne used dialect humor, which was very popular then, to entertain but also as a form of political improvement. He was a classic product of the Progressive Era and brought a certain jaundiced kind of optimism and ability to laugh to a movement not noted for is sense of humor.

Dunne was born in Chicago in 1867 to parents from County Roscommon in Ireland. Largely because of his mother, he got a decent education for a young Irish boy of that generation. He went to work for one of the many Chicago newspapers while just a teenager. A quick learner, he rose fast in the newspaper business and in his twenties was covering baseball, America’s most popular sport, which was being featured prominently in the press. He is often credited with creating the term ‘southpaw’ to describe a lefthanded athlete, especially a pitcher.

Beginning in 1895 he started writing a column featuring an Irish bartender-cum neighborhood philosopher named Martin Dooley, commonly referred to as just ‘Mr. Dooley’ and one of his customers, Mr. Hennessy. Over a 20 year period, he produced 700 of the Mr. Dooley columns, along with a few books collecting these columns of which the best is Mr. Dooley in Peace and War.

The setting was the poor Chicago Irish neighborhood of Bridgeport and featured a list of Irish and other characters who were typical stereotypes: Dock O’Leary, the bearer of all medical wisdom, the neighborhood gossip, Hogan, Father Kelly, the parish priest and font of good judgment, Hip Lung, the Chinese launderer. There was even an African American character: ‘that gr-reat naygro poet, Immanuel Kant Gumbo.’

The columns almost always opened the same way with Mr. Dooley behind the bar, usually reading his newspaper and commenting on an issue of the day to Hennessy. Everything was done in the broadest Irish brogue dialect. Hennessy was ‘Hinnissy’ and was used as a stooge for Dunne as Mr. Dooley pondered the issues of the day. (I often thought that Jackie Gleason’s television sketch ‘Joe the Bartender’ was based on Mr. Dooley. Gleason’s stooge was ‘Mr. Dinniney,’ and the focus of Joe’s observations was ‘Mr. Dinniney” which is not too far from ‘Hinnissy.)

The use of dialect in humor was popular at the turn of the century and can put people off today. George Orwell had a solution to this type of problem when he discussed Rudyard Kipling’s use of cockney slang in his poetry about the British soldiers in India. Simply read them in straight forward English Orwell wrote and they still maintain their power. The same procedure works for Mr. Dooley.

Topics that Mr. Dooley dealt with included the Spanish American War, Woman’s Suffrage, the Tariff, the Hague Peace Conference and Teddy Roosevelt, among others. TR was a particular favorite of Dooley’s, always referred to a ‘me frind Tiddy Rosenfelt.’

Roosevelt was in fact a great admirer of Dooley’s and the two became good friends despite Dooley’s jabs at TR’s policies. For example, he said that Roosevelt’s book on his experience in Spanish American war shouldn’t be titled The Rough Riders but ‘Alone in Cuba.’

Mr. Dooley’s political observations became famous because they captured an era of American politics that was rough, brawling and passionately patriotic. “Wear-re a gr-reat people,” said Mr. Hinnissy.” “Wear-re,” said Mr. Dooley. Wear-re that. An th best iv it is, that we know it.” This perfectly captures the attitude of the American public as it began flexing its influence throughout the world. Interestingly, one of his most famous quips has a certain pertinence today: “the Supreme Court follows he eliction returns.”

A couple of his other observations on politics and life have become popular without people knowing where they came from. “Politics ain’t bean bag,” and one that is often thought of as the essence of serious journalism. “Stories are meant to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” One that shows his jaundiced commentary at its best is: “trust everybody but always cut the cards.”

When Dunne wanted to make a political point, he would turn to his creation. Dunne, for example, was a strong supporter of women’s suffrage at a time when that was viewed as ridiculous by many males. Dooley tells “Hinnissy” that if women want the vote, they can have his. “tis old, but it’s trustworthy an’ durable. It may look a little th’ worse f’r war fr’m being’ hurled again a republican majority in this countrhry f’r forty years, but tis all right.”

Dunne also was a staunch foe of the imperialist urge that spread throughout the nation at the time of the Spanish American War. To those who wanted to improve the lot of what Dooley called the “subjick races,” he told Hinnissy. “We’ve been awfully good to thim. We sint thim missionaries to teach thim th’ error iv their rellligyon…An’ with the missionaries we sint sharpshooters that cud pick off a Chinyman…at five hundred yards.”

Mr. Dooley’s popularity began to fade and after 20 years of peppering the public with his comments, Dunne wanted to write serious journalism. Although nothing he wrote for the magazines that flourished in the first quarter of the 20th century ever came close to the success and popularity of Mr. Dooley.

Dunne’s type of humorous journalism is out of place and would doom him today. Dunne’s successors in his type of political humor, Mort Sahl or Lenny Bruce had a harshness and bitter cynicism to their commentary. They had their moment in the 1950s and ‘60s’ but faded and seem dated today. Mr. Dooley can still be read and enjoyed because at heart he loved the characters he was poking fun at.

In any case, in today’s cancel culture, he wouldn’t stand a chance.

John Rossi is Professor Emeritus of History at La Salle University in Philadelphia.