Sometime shortly after the Good Friday Agreement I was asked to say a few words about the distinctive contributions of John Hume and Seamus Mallon at the end of a local function. There seemed to be some tension between these two leading politicians at the time and people were looking to understand the distinct role for each.

I suggested that the difference between Hume and Mallon was the difference between Plato and Aristotle. I could sense an immediate discomfort, but quickly told them that it was a very simple distinction, and that the themes of these great thinkers was straight forward enough.

Plato created the grand original design of Western thought — the theory of forms, of ideas, that the physical world is a pale imitation of the authentic eternal world and he presented the notion of the immortality of the soul. Someone later said that all philosophy afterwards could be described as footnotes to Plato.

Aristotle, equally brilliant, came from the opposite direction, the concentration of the world around us and his resolution of the outstanding problems of human existence was developed from that perspective. Their combined work dominated western thought for two thousand years.

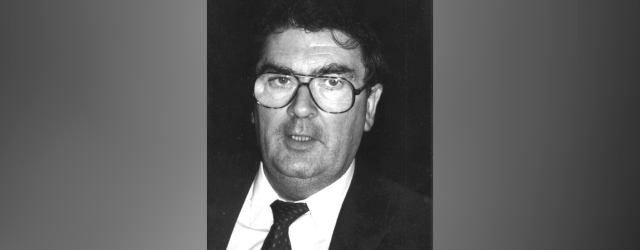

John Hume, who died on August 3rd last, was the greatest figure in Irish politics maybe in the past hundred years. Since the fall of the Sunningdale Executive in 1974 following the Loyalist Worker Strike, Hume was adamant that there could be no internal Northern Ireland resolution, that it had to involve a much wider formula — the threefold dynamic of an Irish involvement, a UK involvement and an Six County involvement.

To achieve this he had to convince London, Dublin, Washington and Belfast that his scheme was the only one. Parallel to this, there had to be an end to the Troubles, a ceasefire from all paramilitaries. He almost single handedly convinced Washington to adopt this three-fold approach and through his US contacts pressurised the Thatcher Government to sign the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, the first big break.

It took him over ten years of endless struggle to bring London, Dublin, the overall US involvement and the parties in the North to the Table, and to convince the IRA to move from the gun into constitutional politics.

The Hume-Adams talks caused him more stress than anything else as it activated the dark side of Irish tribal politics and Hume was badly vilified by armchair prophets and editors in Dublin — there have been many mea culpas in recent weeks from these same sources since Hume’s death, but at the time some were merciless.

So the whole grand design of this resolution of Irish politics is his, and it must be remembered that none of those who finally came to the table were willing partners at the beginning. He was also a man with a great social conscience and divided his Nobel Prize money between two charities in Derry , the Catholic Vincent de Paul and the rotestant Salvation Army. He was also a founder of the Credit Union in Ireland, created to relieve the serious poverty he saw all around him.

Hume invited me out to Strasburg for a week in 1982 to see the workings of the European Parliament there. He was starting to put his strategy into shape even then and kept emphasising how the Europe that used to tear itself apart had now come together in a totally new manner and that this had to be the template to the Irish solution.

Seamus Mallon’s emphasis was on how this grand design could be made a reality on the ground, that participation must come from the inside outward, that is, from the moderate centre parties in the full spirit of the Good Friday Accord and not in a forced marriage between Sinn Fein and the DUP, as eventually happened with all its volatility.

Mallon also felt that a United Ireland could be very much an empty vessel if there was not a fresh overall sense of destiny regarding a new age of intellect and art and Ireland be a centre of European revival in the manner of the old Monastic Age.

So two political Irish giants have departed the scene within six months of each other. But Hume, liked Plato, remains the great original shaper of things, the activator of the Peace Process that has transformed life on this island.

I was actually in Derry on the day of his funeral having booked a few days family outing there a month earlier as the first tentative trip since the outbreak of the Covid-19. It was about three o’clock, several hours after the, and we were driving past Celtic Park in the city when I noticed the cemetery to the left and drove in instinctively as some mark of respect. I saw a few people standing around a grave. It was the fresh grave of John Hume, full of flowers, and we went over to say a prayer.

And I thought of the favourite song he sang with his substantial tenor voice throughout his life, ‘the Derry Air’ and found myself very moved as I stood there thinking of the final verse and how he was speaking to the people of Derry from the grave:

But when you come, and all the flowers are dying,

By Peter Makem

If I am dead, as dead I well may be,

You’ll come and find the place where I am lying,

And kneel and say an Avè there for me.

And I shall hear, though soft you tread above me,

And all my grave will warmer, sweeter be,

For you will bend and tell me that you love me,

And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me.