By Bob Gessler

President, Board of Directors, Irish Memorial

The members of the Irish Memorial Board and I are saddened by Glenna’s passing. The Irish Memorial had an incredible team of artists; the evocative landscape by Pauline Hurley-Kurtz, the beautiful design elements of Patricia McElroy and Dermot MacCormack and soulful words of Peter Quinn … all of which work off of the glorious sculpture by Glenna Goodacre.

Her hands gave life to An Gorta Mor and all of its facets. Next time you visit the Irish Memorial, just focus on the faces and see the humanity expressed there, despair, grief, trepidation, relief and joy, yes joy, the hearty welcome of the greeter.

Every time I’m there, I’m brought back to the first time I saw the sculpture in all of its magnitude in Sante Fe. There dominating the entirety of her studio, was this masterpiece in clay. As the board circled it, our faces raised, there was silence, silence that extended seemingly forever, 10 minutes. Fifteen minutes and longer, until finally we regained our ability to speak.

But as gifted an artist as she was, she was an extraordinary person as well, down to earth, warm and welcoming — Glenna was simply a joy to be with. We all became part of her extended family and grieve with them in her parting. We take comfort however, knowing that every day, a new visitor to the Irish Memorial meets her for the first time.

By Harry Connick Jr.

I write this with a very heavy heart. Jill’s mom, Glenna Goodacre, died last night. Jilly says, “I lost my mother, hero and best friend today, and my heart is completely broken. She was one of the most celebrated artists of all time, and yet she always said that her greatest pieces were her two children. I will miss her love, laughter, and humor.” I posted some of Glenna’s most incredible works of art: the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington DC, the Irish Memorial in Philadelphia, and the Sacajawea Dollar Coin. Glenna was a great hero of mine, too – she personified strength and resolve. I’ve loved her deeply since I first met her when I was 22. I love you so much, Glenna. You will always be a role model to me and, more importantly, to our daughters. You will forever be in my heart. Please pray for my Jilly and her family. thank y’all so much…

By Sister James Ann Feerick IHM

Glenna Goodacre was a talented, compassionate artist, who could identify with the sorrows, joys and struggles of humanity. When she was chosen to sculpt the Irish Memorial in Philadelphia, Glenna had the two-fold task to bring to life the tragedy of the Irish people during the Great Hunger, An Gorta Mor, and the triumph of the Irish people as they built a brighter future for their loved ones back home in Ireland. She created 35 life-sized figures whose faces expressed the sorrow, strength and spirit of the Irish people.

To add to the authenticity of this Irish Memorial, she used concepts that were unique to Ireland: the symbols of the Celtic Cross marking the graves of those who died, and the Irish rock wall symbolizing the hard road ahead of them on their journey. The priest, comforting the sick and dying, and finally the triumph of walking down the gangway to the loving embrace of relatives.

Glenna told the story of the Irish people in a magnificent way. She could only do this because she allowed herself to enter into the minds and hearts of the Irish people during this time of the Great Hunger. Glenna Goodacre completed her task, but I prefer to think she called it a labor of love.

Therefore, when we visit the beautiful Irish Memorial, let us remember to tell the story of Glenna Goodacre, and the love she shared for humanity, because her name will be etched in God’s Book of Life.

by Jim White

CEO,Chief Safety Officer

JJ White, Inc. Since 1920: General, Mechanical, & Electrical Construction & Maintenance.

Glenna Gooddacre was the special lady who sculpted a bust of US Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and gave me the opportunity to take Justice O’Connor on a private tour of the Irish Memorial.

The most important aspect I learned about 1845-1849 when one million Irish died from the Great Hunger, was that it was a genocide by the British against the Irish. The British were shipping food out of Irish ports while the Irish were left to starve.

It was not a famine, a famine means there is not sufficient food in the land the farmers are working.

Glenna was delightful and charming. Her kindness in showing the statue to Timmy Kelly was truly touching.

The Philadelphia Irish Memorial is 14-tons in weight. It is the heaviest, biggest, and by far the most magnificent of all of the Memorials in the United States that paid tribute to the countless contributions of Irish Immigrants to the United States.

Also, the Irish have received the highest number of Congressional Medals of Honor of any Immigrant Group, 258.

By Timothy Kelly

I have such vivid and fond memories of Glenna at the Irish Memorial. Eileen, Timmy and I were standing at the Memorial where the woman has a shovel and is digging, with the little boy next to her. I was explaining to Timmy what was going on, the woman digging for potatoes, and the child looking on with great hope.

As I was explaining, Glenna came over and introduced herself to Eileen and Timmy and began telling us about the sculpture. With that, Glenna asked for permission to pick Timmy up and put him on the sculpture, of course we said yes.

Glenna got up on the sculpture with Timmy and began explaining to him what was going on, then took Timmy’s hands and had him feel the pieces of sculpture. While Timmy felt the various pieces, the woman, the child, the shovel, the hole in the ground, Glenna narrated the story behind each piece.

I remember Glenna being so gentle, caring, paitient and very soft spoken while explaining everything to Timmy. What a remarkable scene this was, Glenna Goodacre, the creator of the sculpture, slowly, patiently and I would say, lovingly bringing this incredibly beautiful piece of art to life for Tim and in a very different way for Eileen and me.

It was an incredibly powerful and touching moment that left us with memory of a lifetime. We stayed in touch with Glenna for a couple of years after the dedication of the Irish Memorial. She wanted to know what Tim was up to and was always happy to hear about his “gigs.” May she rest in Peace.

Kathy McGee Burns

Past President and Board Member of the Irish Memorial

My introduction to the Irish Memorial started early when, as president of the Donegal Association, I was asked to solicit a donation. My organization knew well the plight of Donegal during An Gorta Mor. We had no idea how awesome that sculpture was going to be.

My love affair with the Irish Memorial started on an autumn night in 2002. They were going to unveil this piece of art. It was to be held in an old electric generation station in Chester, Pa., soon to be a luxury office complex.

The exterior had been beautifully landscaped for the event but the interior, with its steel walls, had not been touched.

We first went to Mass said by the Rev. Nicholas Rashford, president emeritus of St. Joseph’s University. The room was dank and had the feel of a room where one would wait to board a boat during the 1800’s in Ireland.

After Mass, we went into the main area and crowded around a huge mass, centrally located and covered with a tarp. The pipers droned out traditional Celtic music and the audience was mesmerized. Suddenly, the tarp rose from what seemed like the sea and a ship appeared, mystically!

There were so many images to deal with: the struggle to board the ship; the Celtic crosses for those who lost the struggle; the toddlers nestled in their mothers’ skirts; and finally the look of hope from the gentleman who makes his way down the gangplank.

No one left the night the same.

Thank you, Glenna Goodacre, you have, with your hands, written our history. You have shown Irish Americans the despair we left, the journey to Amerikay and our success to build a Memorial to it.

You, Glenna Goodacre, will be remembered by us for a long time.

By Tom Keenan

I only met Glenna once, at the unveiling of the Irish Memorial in Chester, PA. As I stood on the stage, I watched her reaction to the crowd as the sculpture was being unveiled. She looked like a parent watching a child at their first Christmas. She was overwhelmed with joy. We love her present to the city as much now as on that day.

As the Memorial photographer, I have climbed all over the sculpture. Looked into the faces as if I was looking into the past. It has made me weep, smile proudly and look inward at my own mortality.

Everywhere on the Memorial, you can see Glenna’s fingerprints as she molded the clay. Glenna also left her mark on all who behold this wonderful tribute to our history.

By Thom Nickels

A Conversation with Jim Coyne

The creator of Philadelphia’s Irish Memorial, Glenna Goodacre, died in her home in Santa Fe, New Mexico on April 13, 2020. The cause of death was natural causes. Goodacre, 80, is survived by her husband, attorney C.L. Schmidt and her two children, model Jill Connick (married to singer Harry Connick, Jr.) and son, Tim Goodacre.

Goodacre’s work is world renowned. She created the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington honoring the 11,500 women who served in that war. In the city of Austin, Texas, one can see her piece, Philosopher’s Rock, depicting a small group of elderly men in a discussion circle. Her work, all figurative in design, has been described as “informal, languid in repose but vigorous in intellect.”

Her sculpture of Sacagawea, the Shosone woman who guided Lewis and Clark during their historic expedition — Sacagawea is depicted with her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau strapped to her back — is yet another example of a body of work that would not have been possible had Goodacre allowed a college art teacher to influence her.

That teacher, as Goodacre has stated in several interviews, advised her not to take up sculpture because she had no talent for three dimensional objects. To prove his point, the teacher gave Goodacre a ‘D’ as a final grade, expecting her to disappear into the stratosphere of another profession.

Goodacre stated that it took her ten years to rid her mind of the teacher’s dour pronouncement (having come of age in a time when students always believed their teachers). Later on, as a successful artist, she was able to give lectures and tell her audiences that “Success is the best revenge.”

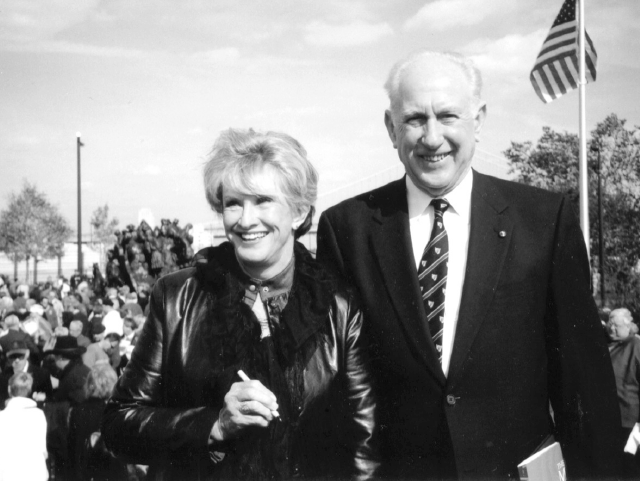

The name, Glenna Goodacre, conjures up the very best in vibrations. As a person, she was every bit that and more, as I discovered when I talked with Jim Coyne, known as “The Father of the Irish Memorial,” who told me that Goodacre “was a lovely person, a great lady and she was a highly talented sculptor; she was pleasant and she had a great sense of humor.”

The idea for an Irish Memorial in Philadelphia goes back to 1989. Coyne, who was the past president and board member of the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick at the time, recalls how fellow board member, Dr. Dennis Clark, told him that there was only one memorial to the Irish starvation “in this hemisphere and it’s in Canada.”

Since the anniversary of the starvation was coming up in 1995, Coyne and Clark decided to propose the idea of a memorial to the Friendly Sons. Coyne and Clark’s motto became, “We’ll get something going.”

When the idea was presented to the Board, it was agreed that it sounded like a good idea. Each member was then asked to write a brief description of what they thought the memorial should be. All agreed that it should be about “how the potato crops failed and how the Irish starved.”

Board member Jerry Kelly reminded the group that there was much more to the story than that. “There was a long history of poor handling of the Irish people,” Coyne said. “They had been under submission of the crown of England for 1,000 years and during that time the English came in and took all the valuable land and pushed the Irish to where the land was poor.

So when the potato crop failed, people had only that to develop for food. There was no famine. Ireland was exporting food. People were being starved to death.”

The goal was the have the sculpture in place by 1995.

“Needless to say we went way beyond that,” Coyne said. “We had a difficult time raising money.” One hundred invitations were sent out to artists to submit design ideas. This was in the early 1990s. Five finalists were selected.

“Then we had a meeting with prominent Irish people in Philadelphia to evaluate the concepts and select the winner. Glenna was the unanimous choice to provide the Memorial. This was in 1996. In 1997 I told Glenna that she had been chosen and in 1998 we signed the contract.”

Coyne told me that Goodacre did extensive ground work before beginning work on the design. “She went to Ireland to look around and get an idea of the scope of things. She looked at the ship Jenna Johnson and she consulted with marine experts in Mystic Harbor in Connecticut, in San Francisco and New York. She did a lot of preliminary work on her own to make sure what she did was accurate.”

Coyne recalls how Goodacre, while working on the Memorial, visited Philadelphia on a regular basis. “There was a lot of correspondence back and forth between her organization and ours.”

The unveiling of the Memorial took place in October 2002 at a former electric generating station in Chester, Pennsylvania, hosted by Michael and Jeanne O’Neill of Preferred Real Estate Investments, Inc. Coyne says the place was huge, perfect for such an event. The actual installation and dedication of the work took place the following year in October 2003.

In 2013, the Memorial was cleaned and sandblasted but refurbishing sans sandblasting takes place every year. “It gets a protective coating put on it,” Coyne said.

The landscaping around the Memorial was engineered to resemble the terrain in Ireland, Coyne said, complete with stone fences. “We have a lady named Pauline Hurley-Kurtz, a professor at Temple University, who handles the landscaping.”

I asked Coyne if he and Goodacre had kept in touch since the dedication of the Memorial in 2003.

“We would always send Christmas cards,” he said.