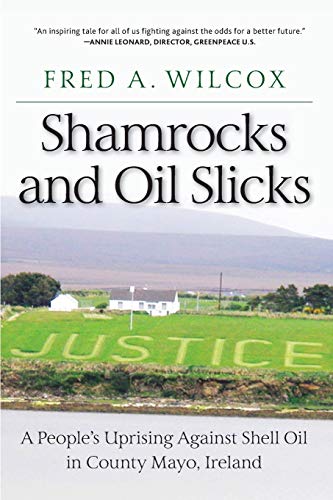

Shamrocks and Oil Slicks:

A People’s Uprising Against

Shell Oil in County Mayo, Ireland.

By Fred A. Wilcox.

Monthly Review Press, 2019

Reviewed by Ellie Harty

In 1999, Professor Mark Garavan was teaching a course in ways to preserve and enrich County Mayo’s extraordinarily beautiful coastline through eco-tourism. He also wanted to voice his concern about a new threat: a refinery and gas pipeline Shell Oil (which had taken over Enterprise and other oil companies) was planning to develop off that very coast and six miles inland.

The dilemma he and Mayo residents were facing was profoundly rooted in Irish history of oppression, of love of land and sea, and its determination to modernize, i.e.: the incomprehensible madness of anyone agreeing “to support building an experimental gas refinery right in the middle of ancient beauty” versus the Irish people’s historical determination not to appear backward: “Any opposition to all this would be giving the wrong signal, as though Ireland wasn’t open for business.”

Reactions and analyses such as Mark Garavan’s and those of many others in and around Mayo have been preserved thanks to Fred Wilcox’s collection of stories of actual residents who either protested and suffered or witnessed and recorded what happened when they and other brave individuals dared to confront a predatory giant corporation, a corrupt local and national government, an out of control police force, an acquiescent Catholic Church, and, most tragically, their own neighbors’ betrayals and abandonment.

Wilcox begins by clearly outlining Shell’s initial promises: jobs, huge payouts to individuals and communities, better roads and schools for the impoverished areas, modernization, all without hurting the environment nor marring the natural beauty. What Shell spokespeople neglected to mention was, Wilcox notes: “The pipe will be buried in unstable soil, run through farmers’ fields, and be dangerously close to private homes. Pressure inside the pipeline will be so high that in the event of an accident, families will be incinerated in seconds.”

Fortunately, some people did recognize that a new and dangerous “colonial” power had invaded Ireland once again, and they were determined to fight, risk beatings and imprisonment, even die, to stop it. The protesters known as the Rossport 5 were especially determined and became national heroes in the process. Their story is the one Wilcox tells in great depth. Willie Corduff, for example, along with four generations before him had lived on the Mayo farmland through which Shell planned to lay its massive, highly pressurized gas pipe. When the Shell agent offered Willie significant money, emphasizing: “You can get a better farm,” Willie replied, as so many Irish had before him, “My heart and soul was here since I was a kid. How could I go somewhere that would mean nothing to me?”

All of that history and dedication to the land and sea meant nothing to Shell and, according to the author, to the local councils and officials bought off, national government watchdogs bought or scared off, church officials bought or cajoled off, police bought and ordered off. As for the pesky resisters holding up its trucks and equipment, preventing employees from entering their lands, Shell offered more generous compensation/bribes, attacks by thugs and police, and an injunction aimed specifically at only the worst, the Rossport 5, who, in violating court order, went to prison.

Shell’s last tactic, however, backfired. The imprisonment of Irish farmers and citizens defending their land aroused the country from its apathy. Willie Corduff even won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for his actions in combatting huge environmental challenges in spite of great personal risk. Shell’s tactics were exposed and reviled and it shut its Mayo operations down…temporarily.

The author supplements Willie Corduff ‘s story with those of other courageous individuals: a fisherman who was beaten, imprisoned, and boat and equipment destroyed by “pirates”; a resident who videotaped protests and sent them out to local and national media; a journalist focusing on Shell and resisters who mysteriously was “laid off” after fourteen years; a local scholar who exposed, in Shell’s Environmental Impact Study, its plan to deliberately dump toxic chemicals into the bay; plus the stories of innkeepers, musicians, and teacher/activists.

Shell ultimately prevailed. The author evocatively describes its facility in Ballinaboy: “A huge firey middle finger thrusts at those who waged a prolonged struggle to keep Shell from building its refinery…”. I found passages like this one compelling and salute the author for his imaginative descriptions. I also thought he effectively chose which quotations best reflected the intrepidness of the people speaking as well as their insights and particularly Irish humor.

Less successful were the often marginally relevant analogies he cited, especially his overly lengthy delving into the Nuremburg Trials and Mi Lai Massacre as a way to indict brutalities by Irish police — claiming they were “only following orders.” I also wish he had organized the book chronologically rather than each chapter dedicated to an individual’s story, to reduce the repetition that occurred with each retelling of events.

Wilcox did, however, successfully stress what messages the protesters and their stories yield for us today: Ordinary men and women can stand up for rights guaranteed by their constitution, resisting the seduction of great material reward, risking the threat of great physical, emotional, or economic harm. We can all be that brave.