By Frank Dougherty

America’s first used bookstore was a Philadelphia family venture founded in 1836 as a sidewalk stall in Center City. For bookworms around the world, it was known as Leary’s Books, one of the largest such enterprises in the world until it shuttered its doors 50 years ago.

At the time of its demise, Leary’s Books was a treasure trove of a shop with six miles of shelves, showcasing more than 600,000 books, manuscripts and items of collectible ephemera, according to the late Philadelphia Daily News writer Nels Nelson.

Described in its day as Philadelphia’s Pantheon of living and departed writers, Leary’s Books supplied patrons with quality used books for 91 years from its seven-story Center City headquarters at Nine South Ninth Street. The building was demolished decades ago along with the cobblestone lane on Ludlow Street where books were sold from curbside bins. Photograph used with permission from Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Philadelphia Evening Bulletin image, photographer not identified.

When Leary’s went out of business in November 1968, it had its own seven-story building at 9 South Ninth Street, tucked in the shadow of Gimbels Department Store.

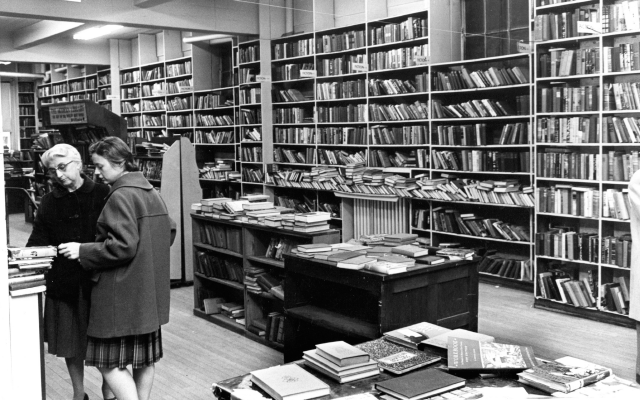

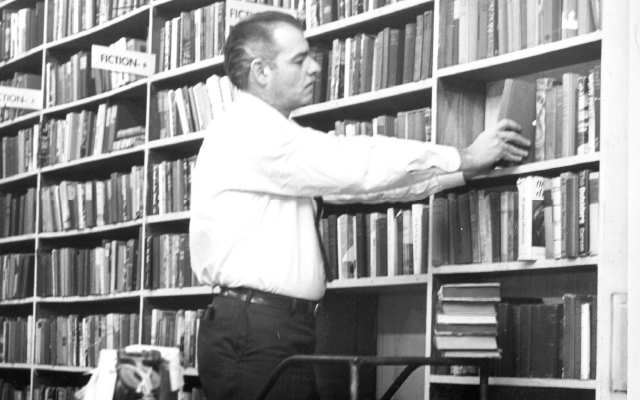

Clerks on ladders leaned against shelves stacked to the ceiling to fetch books for customers. Interior tables overflowed with books. The staff was trained not to interfere with browsers, except to direct them to areas of interest, if so requested.

Books also were offered from outside bins lining the cobblestone lane known as Ludlow street the separated Leary’s from Gimbels. The Leary family moved the business to South Ninth Street in 1877.

It had all the bustle of a North Africa souk with the exception of the outlier table piled high with used paperbacks, a bargain at 10 cents per book.

Upon making a sale, the clerk would place the money into a pneumatic tube and whoosh it down to a cashier in the basement.

After the purchase was registered, change and a sales receipt were whooshed back up to the sales floor.

Leary’s Book Store was so popular that it, too, ended up in a book.

“It would be impossible for any bibliophile to pass this famous second-hand bookstore as for a woman to go to a wedding party without trying to see the bride,” wrote novelist Christopher Morley in The Haunted Bookshop.

A prolific writer, Morley authored more than 50 books. His work was a characteristic mix of charm, wit, and enthusiasm for the English language, according to the Britannica Student Encyclopedia. A resident of West Chester, Morley died in 1957.

Another writer, whose name, alas, is lost in the book stack dust of local history, described Leary’s as: “A Pantheon of living and departed writers (and) the cradle of legend and musty tomes.”

All the Time in the World — Casual browsing was encouraged at Leary’s Books where clerks were trained not to interfere with patrons, except to direct them to areas of interest, if requested. Photograph used with permission from Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA., and the Philadelphia Inquirer/ Daily News Photograph Department. Inquirer image made by photographer James L. McGarrity.

There was, back in the day, an urban legend about Leary’s — one focusing on a mysterious medical student who studied medical books at the store while pretending to browse.

Word was he pocketed his money for medical books, opting instead to study for free, Leary’s medical journals to earn his medical degree.

Despite the past 50 years of hindsight, the jury has yet to rule on this alleged caper!

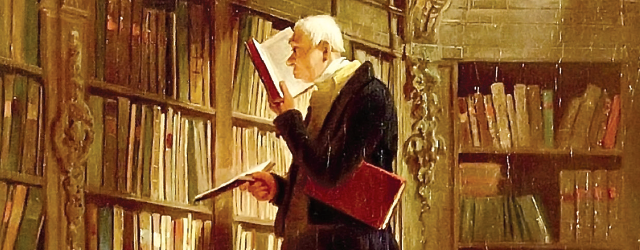

Leary’s trademark was a logo based on an 1850 oil painting appropriately named “The Bookworm” by its creator, German artist Carl Spitzweg. “The Bookworm” icon depicted an old man in knee breeches, a book under one arm, another tucked between his knees, a third open in his hand, perched precariously on a ladder along seven tiers of shelving reaching to the ceiling.

The image was used in Leary’s stained glass show window and appeared as well on the outdoor sign above the Ninth Street entrance.

When the contents of the bookstore were sold by the Freeman Auction House in January 1969, “The Bookworm” stained glass window fetched $4,250 at auction.

The 600-pound outdoor “The Bookworm” sign sold for $200. But the cost to have it safely taken down, then shipped to Michigan, drove that figure closer to $1,000, much to the chagrin of its new owner.

A number of factors contributed to the death five decades ago of this unique and internationally recognized Philadelphia landmark.

“Since so few people (any longer) maintain private libraries, it’s hard to find good used hardback books, and paperbacks continue to cut into sales,” lamented Leary’s general manager Edward R. Poole.

“By the late 1960s, talk radio, chat TV talk shows, and other such diversions began to replace books as a primary source of information and entertainment,” he added.

There was as well a shift in urban dynamics when a large number of city resident browsers who had filled Leary’s aisles relocated to homes and jobs in the suburbs.

When the Freeman Auction House was contracted to sell the contents of the shuttered shop, in an auction in January 1969, an original copy of the Declaration of Independence was discovered inside a scrapbook.

The scrapbook was believed to have been once owned by a Philadelphia lawyer named John W. Dixon. Other items inventoried in the Dixon book included letters dated from 1860 through 1890.

This historical cache of documents was uncovered by a Freeman’s staffer while cataloging Leary’s inventory for the above-mentioned auction 50 years ago.

An antiquities research team certified it as one of seven Declaration of Independence copies printed by John Dunlap, either on the Fourth of July 1776 or the following morning, under the supervision of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

Texas collectors, Ira Corn and Joseph Driscoll paid $404,000 for this historic broadside, then donated it to the J. Erik Jonsson Central Library in Dallas, where it remains to this day on public display.

Information for this profile was obtained through The Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News research library.

The author thanks staffers from both publications for their assistance and kindnesses rendered.

Frank Dougherty is a contributor to the Irish Edition and is a retired reporter/writer who worked for more than four decades with the Philadelphia Daily News

Taking the High Ground — Leary’s Books abounded with clerks on ladders of varying heights as they secured out-of-reach books, cataloged inventory and restocked shelves. Photograph used with permission from Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA., and Philadelphia Inquirer / Daily News Photograph Department. Inquirer image made by photographer Joseph J. Conley.

Leary’s advocate continues to mourn its demise

I was a teenager from the river wards of Philadelphia in 1957 struggling with the challenges confronting an awkward sophomore at Northeast Catholic High School for Boys when I first passed through the welcoming doors of Leary’s Books.

What a revelation for a kid from street corner society!

Leary’s was a big deal, an operation with all the hustle and energy of a Booksellers Row shop on Charing Cross Road in London, or maybe at the Strand in Lower Manhattan.

The place buzzed like a beehive, with busy bee clerks stocking shelves and taking inventory, perched like storks on ladders of varying heights.

I had recently watched the film “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and stopped by Leary’s to purchase a used copy of the Ernest Hemingway novel of the same name on which the film was based.

What I liked best about this Spanish Civil War film was, for the first time in my experience, Hollywood gave the Reds a square deal. It was the story about Robert Jordan and his comrades fighting the fascist forces of Generalissimo Francisco Franco.

When I asked the clerk about the novel, I thought the title sprung from Hemingway’s vivid imagination.

No, it did not, the clerk replied. The English poet and cleric John Donne introduced the phrase to the Western World more than three hundred years earlier in one of his meditations, he explained.

In addition to securing the Hemingway novel, the clerk, a kind and erudite fellow, had in hand a copy of the complete works of John Donne. Until that day, English was my least favorite course at Northeast Catholic.

It carried over from my time at Nativity BVM grade school where English, as taught by the Sisters of Saint Joseph, was diagramming sentences. To this day, I would prefer undergoing a root canal procedure without anesthesia than diagram a single sentence.

When I began to thumb through Donne, I experienced an epiphany, a sudden intuitive leap of what English studies truly was about. It began with: “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

The Hemingway novel drifted off into the ether decades ago, but I still have my Nonesuch Press edition of Donne’s works. Its original list price was $7.50; Leary’s charged me $1.89.

Thus began a beautiful relationship with Leary’s Books which endured through high school, two years active duty in the U.S. Army, and my first decade as a Philadelphia Daily News reporter.

Upon my military discharge in 1966, I rented a garret apartment in the 900 block of Pine Street, five blocks south of Leary’s building.

Not only did I buy books there during twice-weekly visits, it was a great place to introduce out-of-town friends, as well as a new girlfriend, to a totally unique Philadelphia experience.

But like all good things in life, Leary’s, too, came to an end when it went out of business in November 1968. I mourned its loss like a death in the family.

Philadelphians these days have an opportunity to experience a great bookshop by visiting Port Richmond Used Books at 3037 Richmond Street, zip code 19134.

The building opened in 1913 as a silent movie house and currently is owned and operated by Gregory Gillespie, an authority in the field.

Port Richmond Used Books is open from Noon-5 p.m., Tuesday-Saturday. If you plan to visit, telephone first.

It’s a one-man operation and Gillespie is at times away from the business securing inventory.

Telephone: 215-870-5422.