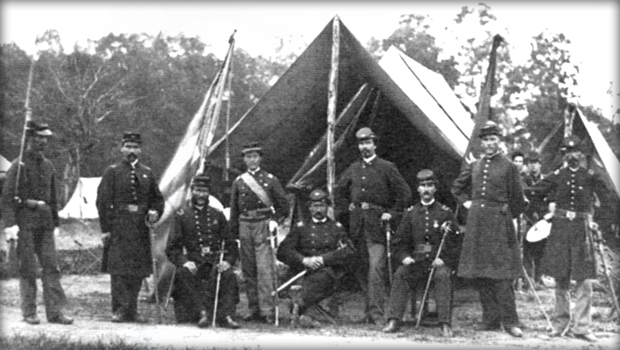

Caption: (above) Officers and staff of the 69th PA Volunteers. – Library of Congress

Irish patriots—Valiant at Gettysburg

By Kerry L Bryan

This year we mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, that critical clash between the Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee, and the Army of the Potomac, under General George G. Meade, who had been ordered to take the high command just three days before this pivotal battle erupted.

In June 1863, as Lee’s forces invaded south-central Pennsylvania, the citizens of this state were in terror that the Confederates would seize the state capital at Harrisburg and perhaps even march on Philadelphia. Never were defenders of the North and the Union needed more.

One of the regiments defending its city, state, and country was that of the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteers (P.V.), whose members were predominately Irish recruited in Philadelphia. These infantrymen proved their mettle long before the paths of the two great armies converged on the small town of Gettysburg, PA on July 1, 1863, and they would continue to perform valiantly until the end of the War. Here is the story of their service.

Formed in Philadelphia in August 1861, this regiment was known as the “2nd California,” due to some political sleight-of-hand. Early in the Civil War, most citizens, whether Unionist or Secessionist, thought that it would be only a matter of months before conflicts would be resolved and that some kind of resolution, whether Union victory or Southern independence would be achieved.

Thus while many young men rushed to enlist to in the hopes of earning what they envisioned as their share of martial glory, a lot of politicians were looking for ways to stake their claim to concomitant fame.

In California some prominent citizens wanted to ensure that their state had a military presence in the East. In a particularly circuitous maneuver, even for politicians, they persuaded London-born, U. S. Senator Edward D. Baker of Oregon to help recruit and lead regiments from the East Coast that would be credited to their Pacific state.

Baker’s biography was likewise convoluted. In simplest terms, we can note that after emigrating to the U.S. from England, he spent some youthful years living in Philadelphia before moving to Illinois. Rising from humble beginnings to become a lawyer and politician in Illinois, Baker became such a close friend of Abraham Lincoln that the Lincolns named their second son Edward in his honor. Apparently restless, Baker later moved to California before he headed up to Oregon, which offered him new opportunities for political success.

Riamh Nar Dhruid O Spairn Iann — “Who Never Retreated from the Clash of Spears.”

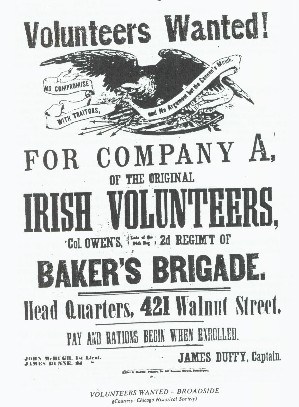

Baker must have had some of the “gift of the gab,” because somehow this native Englishman who was now a West Coast Senator managed to recruit a lot of Irish in Philadelphia, PA, to serve in no less than four of his five “California” regiments. On the other hand, in a city that had been the scene of the burning of Catholic churches and anti-Irish nativist riots just 15 years prior, many local Irish were eager to demonstrate their allegiance and right to citizenship in their adopted country.

Colonel Baker was killed on October 21, 1861, in what became known as the Battle of Ball’s Bluff on the Potomac River, north of Washington, D.C. This action ended in a miserable debacle for the Union participants, and here many of the Philadelphia Irish recruits were blooded and bloodied.

After the death of Baker, Pennsylvania reclaimed its soldiers. The 2nd California was renamed the 68th Pennsylvania, until its men vociferously petitioned to be assigned the number “69” so as to be in synch with the already famous 69th New York Infantry. The “Fighting 69th,” recruited in New York City, was the descendant of the Second Irish Regiment, an 1850s militia group, and as of 1861 had become a proud member of the so-called “Irish Brigade” fighting for the Union cause.

The rosters of these regiments, whether from New York or Philadelphia, read like pages from a Dublin street directory, listing names such as Duffy, McHugh, Kennedy, Moran, Crowley, Mullen, Murphy and more. Like their brothers-in-arms recruited in New York, Pennsylvania’s 69th Volunteers proudly brandished a green battle flag alongside the red, white, and blue of the American colors.

Their green flag, which had been given to the regiment by the Irish citizens of Philadelphia, featured a golden harp topped by white clouds and a yellow sunburst, a field of light green shamrocks, and the Irish motto Riamh Nar Dhruid O Spairn Iann — “Who Never Retreated from the Clash of Spears.”

The men of the 69th P.V. were described as “robust and of hardy habits, and emulous of courage as is the characteristic of their race.” (Bates, Samuel P. (1861-1871). History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65. Vol. II. Harrisburg, PA.: B. Singerly, State Printer.)They would go on to demonstrate again and again their hardiness and courage in battle. They and other units of the Army of the Potomac slugged it out against the Army of Northern Virginia forces commanded by General Robert E. Lee during the Peninsula Campaign in the summer of 1862. They saw heavy fighting at Fair Oaks, Savage Station, Glendale, Gaines’ Mills, Malvern Hill and more. They were involved in various skirmishes leading up to the carnage that was the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862.

There the 69th P.V. was caught in the hail of lead in the infamous Corn Field, but at least that day’s fighting resulted in a technical victory rather than another Union rout. It would not be so three months later, on December 13, 1862, when the 69th P.V. was decimated in the ill-conceived Union assault upon Confederate defensive positions occupying the heights behind the town of Fredericksburg, VA.

By early summer 1863 the surviving members of the 69th P.V. had proved repeatedly that they would not retreat from “the clash of spears.” These sons of Erin were ready to rise to the supreme challenges they faced as a fighting unit on July 2nd and July 3rd at the Battle of Gettysburg, PA.

Occupying a central position on Cemetery Ridge on the afternoon of the 2nd, the 69th P.V. was one of the key regiments that succeeded in repelling an attack led by CSA Brigadier General Ambrose Wright. As ferocious as the assault by Wright’s brigade had been, it was dramatically overshadowed the following day by Pickett’s Charge (more accurately, the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge or Longstreet’s Assault).

After a two-hour, one-hundred gun artillery bombardment to “soften” the Union line, three divisions of Confederate troops — approximately 12,000 men — stepped off in parade lines to cross about 1,000 yards of open ground to attack the center of the Union line.

A copse of trees, known today as the “High Water Mark,” was their visual point of reference, the focal point of the charge. And positioned immediately in front of those trees were the companies of the 69th P.V.

The Confederates dressed their lines to come together for a concentrated attack at the “Angle” a point in the Union line where it formed a 90-degree angle behind a low stone wall. Defending the Angle was the 69th P.V., which was just to the left of fellow Philadelphia Brigade regiments, the 71st, 72nd, and two companies of the 106th P.V.

As the Confederates’ stately march turned into a ferocious charge, the men and artillery defending the Angle poured devastating fire into the fast approaching ranks of the enemy. Despite severe losses, some of the Southern troops reached the stone wall of the Angle. CSA General Lewis Armistead led the Confederate attack with a group of about 200 men, who briefly succeeded in piercing the lines of the 69th and the 71st P.V.

Savage hand-to-hand combat erupted until General Armistead was mortally wounded, and with the help of reinforcements from the 72nd P.V., the Confederate advance was finally halted. Other nearby Union regiments then quickly jumped into the breach, so that the Confederates who had crossed the wall were now outnumbered and cut off from any possible reinforcements.

Lee’s audacious battle plan had failed, and the Battle of Gettysburg emerged as a decisive Union victory. Although the war dragged for almost another two years, never again would the Confederate cause come so close to the possibility of success.

For its role in defending the Angle and defeating Pickett’s Charge, the 69th P.V. earned the proud sobriquet, the “Rock of Erin.” But that title came at a terrible cost: the 69th had 258 officers and men when they arrived at Gettysburg. There, in just two days, it incurred 143 casualties: 6 officers and 36 men killed, 7 officers and 76 men wounded, and 2 officers and 16 men taken prisoner.

After Gettysburg the 69th P.V. went on to fight bravely in almost every important engagement of the Army of the Potomac until Lee surrendered at Appomattox, VA, in April, 1865. After participating in the grand victory parade reviews held in Richmond, VA, on May 2 and in Washington, D.C. on May 23, the surviving members of the 69th P.V. were mustered out of service on July 1, 1865. The lads of the Rock of Erin had served their new country valiantly, while upholding Irish pride and honor.